Pomponio Algerio and His Resolute Faith

Pomponio Algerio and His Resolute Faith

Most tourists to Rome stop by Gian Lorenzo Bernini's Fountain of the Four Rivers, in Piazza Navona. Some drop a coin in the water and make a wish. Hardly anyone is aware that in the same square a young Italian man was boiled in a cauldron of oil, pitch, and turpentine for his religious convictions. And yet, the man’s young age, stubborn refusal to recant, and astonishing composure during that final, agonizing ordeal, have contributed to imprint his name in the history of the Protestant Reformation.

Algerio was born around 1531 in Nola, near Naples, Italy - the same birth-place of another famous dissenter, Giordano Bruno. That general area was also where a Spanish Reformer, Juan De Valdes, held a Protestant-leaning conventicle. Quite possibly, Algerio had already been exposed to dissenting ideas by the time he moved to the university of Padova (or Padua, as it is known outside of Italy).

In Padova, he lived with other students and professionals (including a physician and a jurist and his wife) near Porta Portello, the main city gate. More than simple room-mates, these people shared a desire to read new publications and join recent discussions.

It was not unusual. The University of Padova was known for its free exchange of ideas (which might have been a reason why Algerio moved there). The Italian Reformers Pier Paolo Vergerio and Peter Martyr Vermigli were famous alumni.

All this changed in 1555 with the election (by a slight margin) of Gian Pietro Carafa as pope, with the name of Paul IV. The mastermind behind the 1542 re-institution of the Italian Court of Inquisition, Carafa was determined to stamp out any ember of dissent. He was quoted as saying, "If our own father were a heretic, we would gather the wood to burn him.”[1]

Little is known about Algerio and his life. He is simply described as a young man with a short blond beard. From a court deposition, it appears that he was married. He was arrested in his home on May 9, 1555 and sent to the prison called “Le Debite” (“the dues” – originally meant for those who could not pay their debts), near the university.

Refusing to Budge

During three trials held in Padova between May and July 1555, Algerio didn’t pull any punches. He started by saying he didn’t know why he was being tried. “I declare as true the triune God in whom I place all my trust, and likewise confess Jesus Christ as true God and true man,”[2] he said. If he was in error, he was willing to be corrected, as long as the correction was according to the Scriptures, paraphrasing the Apostle Paul who warned the Galatians not to believe anyone – even an apostle of an angel of God - who preached something contrary to God’s Word.[3]

With clear conscience, he replied frankly to the bishops’ questions. He admitted he didn’t recognize the authority of the pope, since Christ is the only head of the true church. In fact, he thought the Church of Rome could not define itself as “catholic,” since it did not include the entirety of believers.

He said the only sacraments he considered valid were baptism and Lord’s Supper. He also did not believe in purgatory (“Christ is my purgatory”), in the intercession of saints (“Christ is my intercessor and no one else in heaven”)[4], and in the substantial presence of the body of Christ in the consecrated host. On this last issue, he specified he believed that, in the Lord’s Supper, Christians truly “receive the body and blood of Christ, but in spirit,”[5] while the bread retains its substance of bread and not, as the pope said, that the body of Christ remains in the bread until judgment day. Thus, worshiping the bread is idolatry.

On the matter of salvation, he denied the statements of the Council of Trent (then still under way) which included good works as a necessary requirement for justification. “Every Christian and God’s elect is saved and justified through the sacrifice of Christ and not through his own merits, although it’s true that justification by faith cannot be without good works, since a good tree cannot help but bear good fruits.”[6]

His frequent protest was: “I have read the Scriptures.”[7] In fact, he answered most of the inquisitors’ questions by quoting the Bible – even whole chapters. He also demonstrated an impressive knowledge of Canon law (he might have been a law student). He refused to give names of others who shared his convictions.

Since the local authorities were not willing to punish Algerio, Paul IV requested he be extradited to Rome. The authorities bought time, hoping the hardships of prison life and the threats of execution would convince him to recant. Far from doing this, Algerio wrote letters to his friends, confirming his faith. “I have found here – who would believe it! – honey in the lion’s mouth, a joyful dwelling in the dark pit, tranquility and hope of life in the home of bitterness and death, gladness in the infernal abyss.”[8]

“Who could accuse me,” he continued, “and under what charges, if I have obeyed the Lord? Who would dare to condemn me, challenging God’s judgment and the punishment he reserves for those who kill the righteous?”[9]

But accuse and condemn they did. Eventually, the local authorities capitulated and allowed Algerio to be extradited to Rome, where he was tried again (in presence of the pope) and almost surely tortured (it was the common practice for heretics). Since he refused to recant, he was sentenced to death.

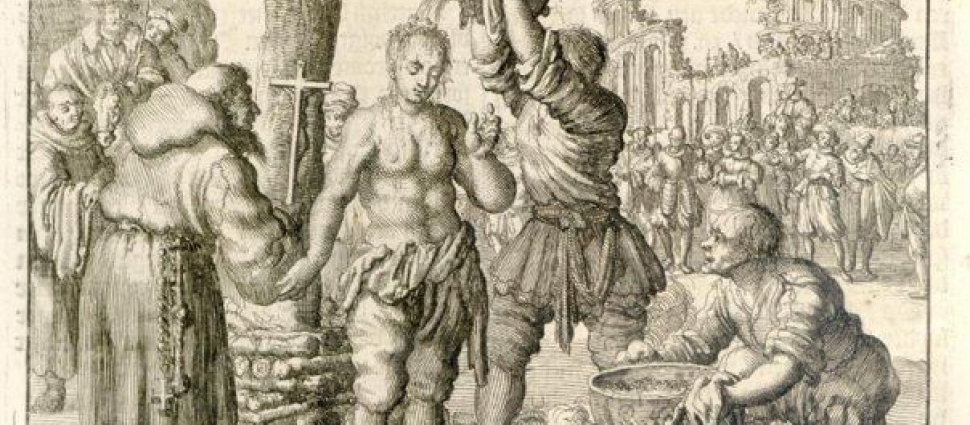

Algerio’s execution on August 19, 1556 shocked the viewers with his composure as he suffered in the boiling mixture for 15 minutes before dying, while repeating, “Receive, O Lord my God, your servant and martyr.”[10] The astonishment of the watching crowd was reported by the Venetian ambassador who was present at the execution.

While the public outrage can only be assumed (such feelings couldn’t be expressed), it exploded in all its fury nine years later, when Carafa died. Remembering the pope’s atrocities and injustices, the people of Rome capped his statue with a yellow hat (similar to the one he forced the Jews to wear), then, after a mock trial, cut off its head and threw it in the Tiber River.

After this, they broke into the three city jails, freeing more than 400 prisoners, then to the prison in the Palace of the Inquisition, where they killed the city’s inquisitor and freed 72 prisoners (including a Scottish Dominican who joined the Scottish Reformation)[11].

The rioting continued for three days and included the burning of the palace and the elimination of the Carafa family coat of arms from all the city’s churches, monuments, and buildings.

In 2008, the University of Padova erected a memorial plaque in Algerio’s honor, remembering how he was arrested and executed “for his religious beliefs, which he inflexibly defended” and how he “faced the stake with exceptional composure and courage.”

[1] Rawdon Brown, ed., Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collection of Venice, and Other Libraries of Northern Italy, Volume 6, Part 2, London: Longman & Co., 1881, 1350, my translation.

[2] Giuseppe De Blasiis, Racconti di storia napoletana, Napoli: Francesco Perella, 1908, 77, my translation

[3] Galatians 1:8

[4] De Blasiis, Racconti 87

[5] De Blasiis, Racconti 85

[6] De Blasiis, Racconti 81

[7] De Blasiis, Racconti 87, et al.

[8] H. PANTALEON Rerum in Ecclesia gestarum ec . Par . II . p . 329 , 332 , quoted in De Blasiis, Racconti 39-40

[9] Ibid.

[10] De Blasiis, Racconti 88

[11] See Aaron Denlinger, “John Craig (1512-1600): From Roman Convict to Scottish Reformer (With Some Help from a Dog),” Reformation21, January 7, 2016, https://www.reformation21.org/blogs/john-craig-15121600-from-roman.php