Elders at the Reformation

What are the important milestones for the Reformation? Traditionally, we date the beginning of the Reformation from Oct. 31, 1517, the day Martin Luther set out his ninety-five theses. That day was indeed a watershed. But we can also point to the importance of several other milestones. The pope excommunicated Luther on Jan. 3, 1521. On April 18, 1521, Luther declared his stance before the Diet of Worms. All three of these events were dramatic, capturing the attentions and imaginations of thousands down to the present day.

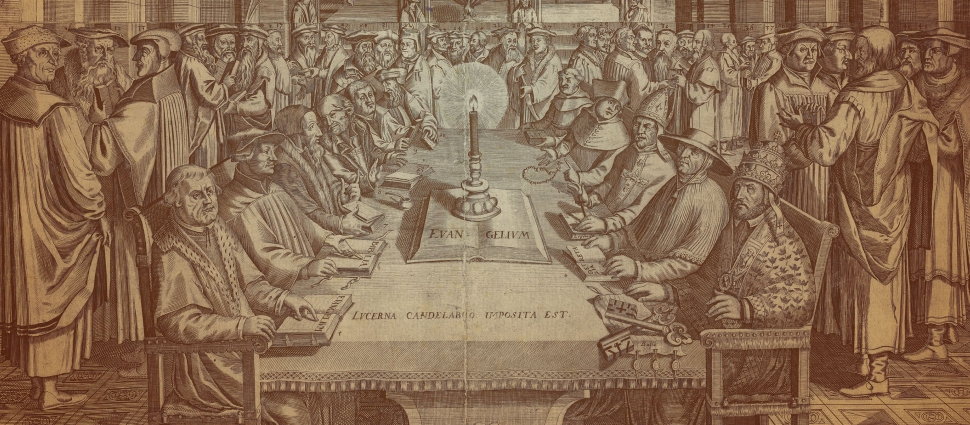

I would like to point to another, later event, which had no drama and draws little attention, but nevertheless proves to have long-range significance. On June 8, 1530,[1] the city council of Basel, Switzerland, considered a proposal from Johannes Oecolampadius to restore the office of elder. Historians have noted that "[T]his was the first time since the time of the Apostles in which the idea of elders was used."[2] In that respect, it was a watershed.

In what way might this event be important?

Doctrine and Practice

The Reformation was driven by a rediscovery of central truths in the word of God. The most obvious of those discoveries was the doctrine of justification by faith alone. This doctrine had been buried (for the most part) for more than a thousand years. It was a key to appreciating the sufficiency of the work of Christ. Christ, not Christ plus our good works, is the basis for our salvation. On the basis of Christ alone, we receive forgiveness and are counted righteous in the sight of God.

The doctrine of justification was the key to freeing people from the bondages of guilt and Satanic accusation. It also freed them from the bondage to an ecclesiastical hierarchy, whose leaders could keep people in fear by refusing to dispense the forgiveness of their sins. Without a biblical doctrine of justification, the threat of eternal judgment or of purgatory hung over the common people.

Luther's ninety-five theses never directly mention the topic of justification. They instead focus on indulgences, and the related topics of repentance and forgiveness of sins. According to the Roman Catholic practice, Christians were invited to purchase an "indulgence," which was a promise authorized by the pope to grant full forgiveness of all sins. But this practice disconnected forgiveness from true repentance and faith in Christ alone.

Indulgences threatened the knowledge of salvation because they gave an erroneous message about the way to salvation. The remedy required a reformation of doctrine—a right understanding of justification, the true basis for understanding God's forgiveness and appropriating that forgiveness by faith alone. But the remedy also required a reformation of practice. The sale of indulgences was a practical issue, not a bare doctrine, yet it reenforced a false message about the way of salvation. For true reformation to take root, the practice of the church must align with her doctrine.

We might picture a situation in which the doctrine of justification is proclaimed with purity, but the practice has not changed. The result is an unclear message; what is verbally affirmed stands at odds with what church practice implies, partly nonverbally.

The Reformation of Practice

All of this helps us better appreciate the significance of June 8, 1530. The office of elder had fallen into disuse since the early years of the church; it was now reconsidered before the city council of Basel. Oecolampadius’s proposal included not only the institution of elders, but specifications for how they were to care for the people of God as shepherds, and how they were to deal with cases needing church discipline.

Oecolampadius’s initial proposal was rejected. But the Basel council did take a small step forward: it drafted a new plan for church discipline.[3] On Dec. 14, 1530, this plan was finally published and implemented for the city, and the next day for the whole province. It appointed four panels of three men each, one for each of the four parish districts of the city of Basel. Each panel was to consist of two men from the Basel city council and one man “from the congregation.”[4]

This was a timid step. In principle, the city council retained full control in its own hands, by appointing two of its own members to each of the panels. But we can still see here a decisive move forward in the appointment of the third panel member who was “from the congregation.” In effect, this third member functioned as an elder. With this, the council took a positive step toward carrying out church discipline in a biblical way. This would be developed further in the Geneva of Calvin’s day, with the responsibility of church discipline invested in the church officers, not the civil authorities.[5]

This key step concerning church discipline has indirect effects on the message of salvation itself. Why? Because the proper appropriation of the doctrine of salvation and justification depends not only on spiritual truth but on spiritual power, the power of Christ’s rule over the church. Teaching must go together with ruling. And ruling in the church is the responsibility of elders, not civil magistrates.

Consider more specifically the work of teaching and of ruling. Spiritual truth is proclaimed in words, from the pulpit. It is also proclaimed in signs, by baptism and the Lord's Supper. Spiritual power is exercised in words, by the power of the word of God that pronounces forgiveness. It is also proclaimed in signs, the sacraments. And the use of the word and the sacraments is supervised by the elders. Under the authority of Christ, these elders are the spiritual rulers in the church. The word of God from the pulpit proclaims free forgiveness, without the need of indulgences. This free forgiveness comes to everyone who repents and believes. But it comes only to those who repent and believe. It does not come to everyone who enters the church building and hears the word of promise.

The elders rule in this discriminating process. They examine people concerning their repentance and faith—or their claims to have repentance and faith. The elders hold the power—the spiritual power—of the keys of the kingdom of heaven: "if you forgive the sins of any of them, they are forgiven them; if you withhold forgiveness from any, it is withheld" (John 20:22 ESV; see Matt. 16:19; 18:18).[6] This power is made manifest, at the most concrete level, by baptism, which admits people to membership in the community of salvation. It is manifested negatively in withholding participation in the Lord's Supper from unrepentant people, and excommunicating them if they continue to refuse to repent.

This power of rule, the power of the elders, when properly exercised, is a powerful reinforcement of the meaning of the word of God. It illustrates salvation at a visible, practical level. The most notorious and scandalous sinner, like the thief on the cross, receives forgiveness in exactly the same way as the people with the most honorable social standing. All alike are forgiven as soon as they place their faith in Christ. The power of the elders in discipline illustrates negatively that free forgiveness never opens the door to continue in sin and not to repent. Excommunication, not merely the verbal warnings against sin, is a necessary gift, provided by the Lord himself, to bring home the meaning of salvation in Christ.

Thus, the answer to indulgences must have two sides, not only one. The two sides are proclamation and rule. Proclamation is an exercise of the prophetic office of Christ; rule is an exercise of the kingly office of Christ. Proclamation takes place as Christ speaks to his people through the teaching office of the church (ministers of the word of God). This proclamation has spiritual power, through the work of the Holy Spirit. So it includes an aspect in which Christ rules over those whom he addresses. Rule also takes place as Christ rules over his people through the ruling office of the church (the elders). The teachers proclaim the free forgiveness of sins, without payment, without any treasury of merit allegedly accruing from the merits of the deeds of the saints. The rulers enact the free forgiveness of sins, without payment, by approving candidates for baptism and the Lord's Supper.

Reformation Reactions

Consider now the reaction of civil rulers to the events of the Reformation. The reaction was mixed. It depended, of course, on whether a particular ruler was sympathetic with the new message of the Reformation. Did he believe it himself? But, to a certain extent, it also depended on issues of power. Civil rulers could see the new wind of the Reformation as a threat to the stability of their own control. If they did, they would try to stamp it out. Or they could see the new wind as a counterweight to the power of the Roman Church, which exerted unwelcome power and sometimes caused a financial drain on their territories.

So civil rulers could be found moving in either direction with respect to the Reformation. But hardly a single ruler can be found anywhere in Europe who welcomed the idea of elders. The appointment of elders—unless such appointments were made by the civil rulers themselves—meant the raising of a new kind of authority, a new kind of rule, that existed alongside their own civil rule and not under their control.

Of course, in earlier times in medieval Catholicism, the civil authorities all along had to deal with the church's authority over the sacraments and excommunication. Some of the popes had withheld communion from a king or prince, or even from everyone in the king's territory, to force compliance. That was one reason why a civil ruler might look with favor on the Reformation as a counterweight to the pope. But the city councils in Switzerland expected the pastors' recommendations for excommunication to be vetted by the council. The council had a say. They were not going to let go of power just because Oecolampadius argued that it was a biblical idea. At the crucial council meeting in 1530, Oecolampadius failed to persuade the council to surrender its power.

Fortunately, that is not the end of the story. In a subsequent article, we consider the benefits of Oecolampadius’s contribution.

Vern S. Poythress is Distinguished Professor of New Testament, Biblical Interpretation, and Systematic Theology at Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he has taught for 45 years.

Related Links

"The Joy of Justification" by Nick Batzig

"Are You Sick? Call Your Elders" by William Boekestein

"Lessons From a Controversial Colloquy" by James Rich

Vital Churches: Elder Responsibility for Their Pastors and Congregational Planning by Wendell Faris McBurney

Reformation: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow by Carl Trueman

Notes

[1] Ernst Staehelin, Briefe und Akten zum Leben Oekolampads, 2 vols. (Leipzig: M. Heinsius Nachfolder, reprint, 1971), #750, 2.460n2, indicates that there is uncertainty as to whether Oecolampadius appeared for his presentation on June 8, 1530, before the Large Council of the city of Basel, or earlier before the Small Council, in May or early June. In any case, the deliberations of the Large Council, and its subsequent ruling on June 8, 1530 (ibid., #751, 2.461-464), took into account Oecolampadius's presentation.

[2] Diane Marie Poythress, "Johannes Oecolampadius' Exposition of Isaiah Chapters 36-37," Ph.D. dissertation, Westminster Theological Seminary, 1992, p. 68, citing Walther Köhler, Zürcher Ehegericht und Genfer Konsistorium (Leipzig: M. Heinsius Nachfolger Eger & Sievers, 1929), 1.284, and Akira Demura, "Church Discipline According to Johannes Oecolampadius in the Setting of His Life and Thought," Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton Theological Seminary, 1964, 86 (see also 90). See also Ernst Staehelin, Das theologische Lebenswerk Johannes Oekolampads (Leipzig: M. Heinsius Nachfolger, 1939), 511. Oecolampadius's proposal included a reference to the Greek word πρεσβύτεροι, "presbyters, elders," clearly indicating that he was basing himself on the New Testament office of elder (Staehelin, Briefe und Akten, #750, 2.454).

[3] Demura, "Church Discipline," 117; see Staehelin, Briefe und Akten, #751, 2.461-464.

[4] Demura, "Church Discipline," 118; Staehelin, Briefe und Akten, #809, 2.537. Oecolampadius's initial proposal was itself a compromise. He proposed to appoint for the whole city of Basel a single panel of twelve men for considering cases of church discipline. The panel was supposed to have four members from the city council, four pastors, and four elders representing the congregations (Demura, "Church Discipline," 85; Staehelin, Briefe und Akten, #750, 2.454). The ideas from his proposal were also presented to a larger circle of Reformed cities in Switzerland, but no one was willing to implement them--at least at first (Demura, "Church Discipline," 92-116).

[5] Demura, "Church Discipline," 176. Even so, at Geneva there were still unwarranted entanglements of church and state. It took centuries to understand the proper limitations of civil and ecclesiastical authority.

[6] Oecolampadius cites Matt. 18:18 in his proposal to the Basel council (Staehelin, Briefe und Akten, #750, 2.449, 456).