Johannes Theodorus van der Kemp – An Unconventional Missionary

Johannes Theodorus van der Kemp – An Unconventional Missionary

The renowned historian Andrew Walls describes Johannes van der Kemp as an unconventional candidate for the London Missionary Society (LMS). At the time of his application, van der Kemp was in fact fifty years old and had both a higher education and a more complicated past than the average candidate. “While most LMS candidates lamented their early sins and misimproved talents and opportunities,” Walls writes, “this ex-dragoon officer really had been a sinner on a fairly spectacular scale. He had also been a deist and a rationalist author.”[1]

Sinner, Deist, and Rationalist

Born in 1847 at Rotterdam, Netherlands, van der Kemp had started his theological studies on the footsteps of his father, a Reformed pastor. After graduation, he instead joined the army, progressing through the ranks until he became a Captain of the Horse and Lieutenant of the Dragoon Guards (a branch of the cavalry).

It was while serving as an officer that he fathered a daughter, Johanna. Since the mother was married, he brought up the child by himself until 1779, when another woman, Christina Frank, agreed to marry him and take on the mother’s role.

Leaving the army, van der Kemp went to Scotland to study medicine, graduating in 1782 from the University of Edinburgh. He practiced medicine in Scotland for a while, earning a reputation as a caring physician, then moved back to Holland.

Throughout this time, he had no interest in religion if not to deride it. Christianity was, to him, "inconsistent with the dictates of reason" and "the Bible a collection of incoherent opinions, tales, and prejudices." He initially admired Christ "as a man of sense and learning"[2] but lost his veneration when he realized that Christ called himself the Son of God.

He did feel the weight of his sins and prayed that God would prepare him, by punishing his sins, "for virtue and happiness." Because of this, he interpreted every misfortune as a punishment aimed at making him a better man. When this didn't happen, he realized that virtue and happiness were out of the reach of his reason. “I confessed then my impotence and blindness to God and owned myself to be like a blind man who had lost his way and who waited in hope that some benevolent person would pass by and shew him the right path.”[3]

Meeting Christ the Conqueror and Prophet

All this changed in 1791 when a boating accident led to the deaths of his wife and his daughter, who was still his only child.

"When the Lord Jesus first revealed himself to me, he did not reason with me about truth and error but attacked me like a warrior and felled me to the ground by the power of his arm. … But as soon as I submitted to him as a conqueror he assumed the character of a prophet, and I then perceived that the chief object of his doctrine was to demonstrate the justice of God in condemning and saving the children of men."[4]

He was pleased to find the same realization in Paul's letters. "Because therein the justice or righteousness of God is revealed from the word of faith so evidently that it excited faith and conviction in the hearer,"[5] van der Kemp concluded.

After this, he was appointed director of a hospital in Rotterdam. There, he worked for the physical and spiritual well-being of the patients, providing them with a catechist for religious instruction.

When the hospital was destroyed as a consequence of the Dutch-French war, he retired to Dordt where he studied Oriental languages. It was there that he heard about the newly-formed London Missionary Society (LMS).

Moved by a transcription of one of their sermons, he contacted the society explaining how he was torn between the desire to participate in missions and that of seeing a similar society in the Netherlands. By visiting the Society in London, he saw both desires fulfilled: he was chosen for a mission in South Africa, and became instrumental in the foundation of the Netherlands Mission Society, based in Rotterdam. A similar society was soon founded in East Friesland.

Mission to South Africa

Van der Kemp moved to South Africa in 1799, settling in Kaffraria, a British colony in the south-eastern portion of the country. By appointment, he was to minister to the Dutch who had been the original colonists. But he couldn’t ignore the local population – the Xhosa who had become, in practical terms, servants of the Dutch, and the Khoikhoi who had been displaced.

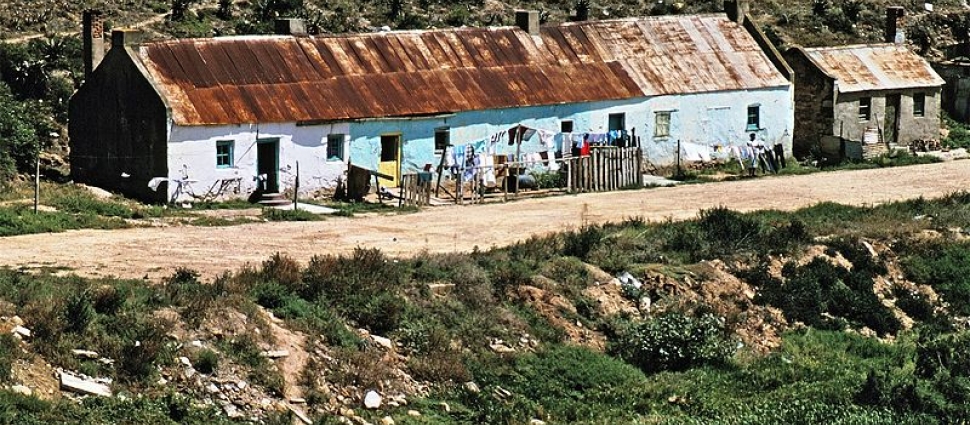

He persisted in his efforts to evangelize these people in spite of slim success and of fierce opposition by the Dutch. In 1803 he founded Bethelsdorp, a mission station near Algoa Bay, where he focused on the spiritual and material wellbeing of the Khoikhoi.

As if his advocacy for the local populations was not unnerving enough for the colonists, he shocked them by adopting the locals’ customs. He dressed like them, lived in a hut with them, and eventually married a Malagasy slave girl.

Most European settlers didn’t understand his behavior. Some were horrified, while some simply thought it unnecessary. Why going down to these people’s level instead of raising them to ours, they thought. A few, misapplying Bible passages on the descendants of Ham, were furious that he would inspire the local populations to seek fair treatment and a dignified status. But van der Kemp wanted to show the local populations that Christ came for them as they were in their culture, and that they didn’t need to become Europeans in order to be Christians.

He and the other missionaries at Bethelsdorp had reason to rejoice in 1807, when King George III of England signed into law the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It was just a first step, because slavery was still legal, but it was a monumental step, affirming the dignity and full humanity of people of all races. Van der Kemp marked the event with a day of public thanksgiving and composed an inn for the occasion.

He died in 1811 of a fever during a trip to Cape Town. He was honored in his funeral and continues to be appreciated for spearheading a concept of cultural and racial appreciation at a time when it was still alien.

To most colonists, he was uncomfortable in his defiance of conventions – a prick in their sides. And yet, according to Walls, “his uncompromising behavior brought the question of race relations onto the missionary agenda, and kept it there.”[6]

Years later, the Scottish missionary John Philip turned England’s attention to the way the colonists abused and mistreated the local South African populations. Although his words gained a more receptive audience, Walls believes that “it is doubtful whether the mission would or could have maintained so firm a stand in a hostile environment without the initial confrontations with Van der Kemp, a man who could not be ignored.”[7]

[1] Andrew F. Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History, Maryknoll, New York: Orbis books, 2002, 209

[2] Memoir of the Rev. J. T,. Vanderkamp, M.D., Late Missionary in South Africa, London: J. Dennet. 1812, 6

[3] Ibid.

[4] Memoir of the Rev. J. T,. Vanderkamp, 9

[5] Ibid.

[6] Memoir of the Rev. J. T,. Vanderkamp, 210

[7] Ibid.