Lord, Have Mercy on Us

Late in 1664 it was apparent the bubonic plague was making one of its unwelcome visitations of Europe by registering in London for an extended stay checking out early in 1666. It varied in the number of victims from month to month, but it survived through all four seasons. Over 80,000 people died of the pestilence at a time when the city population was about 450,000. Its visitation was recorded by diarists Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn who both provide eyewitness accounts of its devastation. Another view of the London plague that is fictional but based on historical sources was published a half century after the fact by Daniel Defoe in A Journal of the Plague Year.

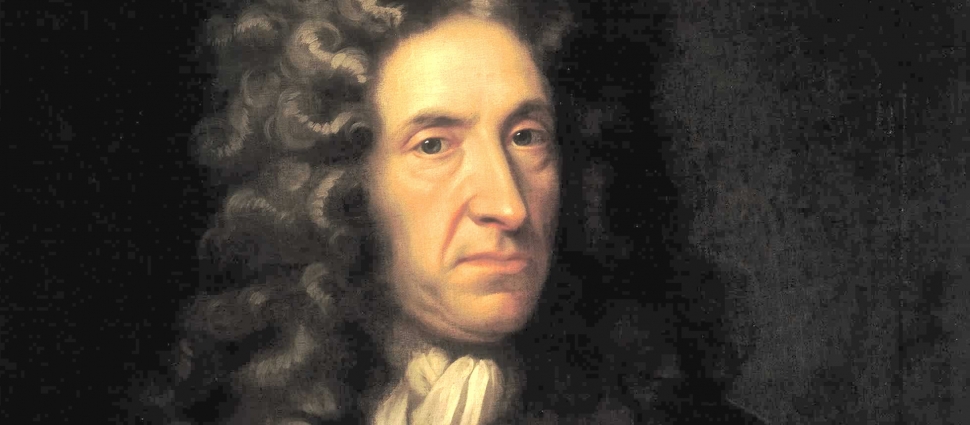

Daniel Defoe was born to his mother whose name is forgotten to history and father James in 1660. James was a butcher for his livelihood and a Dissenter with regards to Christianity. Dissenters, also called Nonconformists, did not participate in Church of England worship but were instead Congregationalists or Presbyterians among others. James and his wife raised Daniel to be a Dissenter. They attended services at St. Giles Cripplegate where Samuel Annesley was the dissenting Church of England cleric. Annesley and two thousand other nonconforming clergy were ejected from their pulpits in August 1662. These devoted men refused to abide by the Act of Uniformity requiring all Church of England clergy to follow the Book of Common Prayer. Accompanying ejection were other hardships suffered by Dissenters such as limited educational opportunities. Daniel could not attend Oxford or Cambridge but instead studied in the Academy on Newington Green directed by Charles Morton. One of Defoe’s classmates was Timothy Crusoe who became a Presbyterian minister and his surname may have inspired Defoe’s protagonist in Robinson Crusoe.

When Defoe completed schooling, he worked in different jobs, became politically active, and boldly expressed his opinions as a pamphleteer. He participated in Monmouth’s failed Rebellion in 1685, and even donned a dark frock and armed himself with a sword cane to serve as a spy. He was not afraid to take on the opposition and was fined, imprisoned, and spent time in the pillory for his politically incorrect opinions. From 1704 until it was suppressed in 1713, he operated the newspaper Review where he published his sentiments in editorials. Defoe continued in journalism until Robinson Crusoe was published in 1719. The tale of a mariner shipwrecked on an isolated island was a great success that led to numerous English reprints as well as translations in several languages. The novel follows a realist-diarist style as Crusoe struggled to keep alive. Defoe’s Dissenter Christianity comes through in Crusoe’s prayers and sense of dependence on God. The same style governs the story in A Journal of the Plague Year as the narrator recounts events in a journalistic style.

Picking up on the marketing opportunity from Europe’s memories of the Marseilles plague in 1720, Defoe began his book at the docks where a ship from Rotterdam was credited with bringing the pestilence. Sickened crew members made their way into London’s ale houses and alleys infecting the population by contact, but unknown at the time was the plague was also transmitted by fleas from rats. While the Lord Mayor, five officers, and others fought person to person infection, the rats were making their ways through dark passages and gutters carrying their infested parasites. Whether it was through personal contact or a flea bite, the plague spread throughout the city.

In the more than three-hundred years since the London plague, the way of impeding propagation of an epidemic has not changed in its fundamentals. Excluding the great advances in science and medicine enjoyed today, stopping an epidemic requires blocking its channels of distribution by closing streets, waterways, ports, and other venues, as well as isolating the infected individuals from others. Once the plague was diagnosed by surgeons from the presence of headaches, fever and buboes—blackened and swollen lymph nodes—there was little that could be done regarding treatment. The key to success was stopping the spread because death was the likely outcome if a person was infected.

A system was needed to stop the plague and the parishes of the Church of England provided geographic areas of administration recognized by Londoners. Each parish was overseen by five kinds of plague officers: examiners, watchmen, searchers, chirurgeons (surgeons), and nurse keepers. These officers carried red wands three feet long that were held so as to be obvious to all. The wands both warned Londoners to maintain their distance and indicated the officers were available for assistance. The quintet of officers combined purpose was to diagnose, isolate, watch over, seek out the deceased for burial, enforce regulations, and keep the uninfected healthy. Once an officer determined a house was with plague, Defoe described how citizens were informed of its infected residents:

That every house visited [by the plague] be marked with a red cross of a foot long, in the middle of the door, evident to be seen, and with these usual printed words, that is to say, “Lord have mercy upon us!” to be set close over the same cross, there to continue until lawful opening of the same house.

If the residents of a house survived the plague by the Lord’s mercy, then the individual had to be isolated for a fortnight. Homes of the recovered and deceased were aired out, perfumed, and purified over a period of time. Defoe said the people that faced the greatest economic hardships were carpenters, jointers, smiths, turners, sawyers, and roof wrights as well as anyone associated with shipping and transport including coopers, sailors, dock men, wheelwrights, sailmakers, and cordwainers. Those who made clothing accessories like hats, gloves, and other bits of seventeenth century fashion had no market because those with means fled to escape the pestilence—vogue accessorizing could not compete with survival. The fleeing wealthy left many servants jobless, while the prosperous that stayed home would not let household personnel in because they feared contracting plague.

At the same time, the pestilence created other jobs in addition to the plague officers mentioned. Graves had to be dug at least six feet deep—and there were unfortunately many to dig—but as the daily deaths increased the Lord Mayor resorted to mass burials requiring larger excavations. It was an especially tragic situation because those working with the victims were highly likely to become victims themselves. Events like bear baiting (taunting bears) and buckler play (sword skills) were prohibited because the crowds of fans provided opportunities to spread the contagion. All plays, gatherings for ballads, feasts, and public dinners were banned.

As the months wore on into the fall other measures were taken including putting out poison to kill mice and rats out of fear they might carry plague-infected fluids to others; unknowingly, the rodent eradication plan was a particularly good idea. The Royal College of Physicians published sheets daily with information about the plague. Those confined to their homes became restless as fall approached and resisted continued isolation, despite the month of September having the highest number of deaths (8,000).

It is not difficult to see that the efforts of Londoners 350 years ago were not so different from what is done currently to stop epidemics; the twenty-first century knowledge, equipment, and facilities are greatly improved. Londoners did the best they could to stem the pestilence using the knowledge and means they had. Their microbiological enemy was a bacterium and not a virus and the presence of rats year-round made ending the epidemic even more difficult.

Defoe’s Christianity comes through in A Journal of the Plague Year as it did in Robinson Crusoe. The government encouraged people “to implore the mercy of God.” One mother prayed to God that her child did not have the plague. As the pestilence increased its victims, they “would go praying and lifting up their hands to heaven, calling upon God for mercy.” One group “went to prayer with all the company, recommending themselves to the blessing and protection of providence before they went to sleep.” One surgeon visited some victims and upon leaving he gave “blessing to the poor in substantial relief to them, as well as hearty prayers for them.” But as Defoe’s account approaches conclusion, he makes a remarkable statement:

In the middle of their distress, when the condition of the city of London was so truly calamitous, just then it pleased God, as it were, by his immediate hand, to disarm this enemy; the poison was taken out of the sting; it was wonderful: even the physicians themselves were surprised at it: wherever they visited they found their patients better; either they had sweated kindly, or the tumours were broke, or the carbuncles went down, and the inflammations round them changed colour, or the fever was gone, or the violent headache was assuaged, or some good symptom was in the case; so that in a few days everybody was recovering; whole families that were infected and down, that had ministers praying with them, and expected death every hour, were revived and healed, and none died at all out of them.

The Great Plague of London was the last major outbreak of the pestilence the city experienced after suffering through several visitations over the centuries. It might be thought Defoe was writing fiction, so maybe his Christian supernatural presuppositions were imposed on the facts. Yet some historians have considered the plague's end spontaneous, as if it just stopped. To be sure, the rats did not pack their bags, board all fleas, and leave town. Other historians say the plague bacteria simply became ineffective for people, while still others attribute its failure to return to a different variety of rats evicting the one that carried the deadly fleas. Even if both these theories and others are true, it does not explain why at that point in time.

God’s grace came forth in mercy. The end of the plague was not spontaneous, but rather it ceased because the Lord answered the prayers of his people. If killing rats and bacterial changes were effective, it was because of the hand of God.

Daniel Defoe went on to live out his life writing, and was graced with the three-score-and-ten years of Psalm 90:10, passing away April 24, 1731. Mary Tuffley and Defoe enjoyed a lengthy marriage, with eight children born to them. He is buried in London in Bunhill Fields which is known as the Puritan necropolis—not only because John Bunyan, John Owen, and Thomas Goodwin are interred awaiting resurrection, but also many other Dissenters of the precisionist persuasion. The memorial on his grave reads, “This monument is the result of an appeal, in the Christian World newspaper, to the boys and girls of England for funds to place a suitable memorial upon the grave of Daniel De Foe. It represents the united contributions of seventeen hundred persons. September 1870.”

Christians today should remember Daniel Defoe.

Barry Waugh (PhD, WTS) is the editor of Presbyterians of the Past. He has written for various periodicals, such as the Westminster Theological Journal and The Confessional Presbyterian. He has also contributed to Gary L. W. Johnson’s, B. B. Warfield: Essays on His Life and Thought (2007) and edited Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War I (2012).

Related Links

Mortification of Spin: "But They Had Everything in Common"

"William Bridge's Ministry of Encouragement in A Lifting Up for the Downcast" by Barry Waugh

"In the Face of Crisis, Fear the Lord" by Christina Fox

"Submit to the Government Serving God to Save Lives" by Grant Van Leuven

"Coronavirus and the Church: Compliant, or Uncreative?" by Terry Johnson

What Is the Church? with Michael Horton, Greg Gilbert, and Robert Norris [ Download ]

Seven Churches, Four Horsemen, One Lord by James Boice

Notes

Both the population of London and the number of deaths were selected from accounts that varied. The copy of A Journal of the Plague Year used for this post is from Longmans’ English Classics series, as edited with notes and an introduction by George R. Carpenter, New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896; this version is from the second edition, was edited by Carpenter with secondary school education in mind, and it includes a curriculum guide. The biography of Defoe on Britannica Online by Reginald P.C. Mutter and the piece in Concise Dictionary of National Biography to 1921, Oxford University Press, London: Humphrey Milford, [1930] were both used with the biography in Carpenter’s Journal edition. I could not locate Defoe’s mother’s name. Daniel was born Foe and he changed his name in later life to DeFoe, thus Defoe currently.