The Logic of Puritan Preaching

The Puritans were driven by Christ-centered expository preaching. God’s Word gave them the grammar; it was as essential to Puritan preaching as phonics for the four-year-old learning to read. And yet knowing what God said in a particular text is not alone sufficient for transformative, God-exalting preaching. God's word, together with proper exegetical and hermeneutical principles, form the "parts" of preaching, but what may we say about the "whole"? How are preachers to bring their exegetical spade-work to bear upon an audience that, according to God's word, is totally depraved and spiritually rent asunder by sin?

It is in response to that question that the concept of dialectic (i.e. logic) becomes important. Dialectic/logic addresses the inter-relatedness of foundational facts, and it is precisely within this inter-relatedness that several important dialectics emerge in Puritan preaching. These dialectics are evidential of specific ways in which the foundational facts of Puritan preaching are crystallized and brought to bear upon the parishioner's mind.

Organizational Dialectic

"The receiving of the word consists of two parts: attention of mind and intention of will." — William Ames

The very essence of the dialectic in the trivium schematic is the organization it provides for the individual parts. Organization gives a global perspective to what would otherwise be isolated localities. Students arrange sentences and paragraphs; preachers arrange sermon outlines. Just as Greek philosophers were expected to learn the laws of logic, Puritan preachers were expected to learn the laws of sermon organization. Puritan sermons were characterized by careful methodology and organization. They were intentionally logical, even “logic on fire” (to borrow a phrase from Dr. Lloyd-Jones). The Puritans were deeply concerned about form and structure within their sermons, perhaps even to a fault at times. Excesses notwithstanding, contemporary preachers would do well to share this Puritan zeal.

At the end of The Art of Prophesying, William Perkins offers a suggested preaching format that clearly displays the characteristic of Puritan sermons. Perkins advocates that preachers ought to:

- Read the text distinctly out of the canonical scriptures.

- Give the sense and understanding of it being read, by the scripture itself.

- Collect a few and profitable points of doctrine out of the natural sense.

- To apply, if he have the gift, the doctrines rightly collected to the life and manners of men in a simple and plain speech.[1]

Because of their deep and reverential commitment to the Scriptures, the Puritans often belabored certain points of doctrine with seemingly excessive detail and scriptural proofs. They did this not because they loved tedious speech, but because they

"...felt constrained to proceed to buttress each doctrine with the examples and testimonies of Scripture... to ensure that the doctrine adduced from a specific text had the whole weight of Scripture behind it."[2]

Ryken provides two very helpful windows into the organizational framework of a puritan sermon:

“The Puritan sermon was planned and organized. It may have been long and detailed, but it did not ramble. It was controlled by a discernible strategy and it progressed toward a final goal. The methodology ensured that the content would be tied to Scripture, that the sermon would involve an intellectual grasp of the truth, and that theological doctrine would be applied to everyday living.”[3]

“The Puritan sermon quotes the text and "opens" it as briefly as possible, expounding circumstances and context, explaining its grammatical meanings, reducing its tropes and schemata to prose, and setting forth its logical implications; the sermon then proclaims in a flat, indicative sentence the "doctrine" contained in the text or logically deduced from it, and proceeds to the first reason or proof. Reason follows reason, with no other transition than a period and a number; after the last proof is stated there follow the uses or applications, also in numbered sequence, and the sermon ends when there is nothing more to be said.”[4]

The Puritans stressed organization because they believed that grace enters the heart through the mind. According to Packer,

"God does not move men to action by mere physical violence, but addresses their minds by his word, and calls for the response of deliberate consent and intelligent obedience. It follows that every man's first duty in relation to the word of God is to understand it; and every preacher's first duty is to explain it."[5]

It is the preacher's job to explain the Bible in a clear, organized manner so that the sheep may draw near and feed upon it.

Applicatory Dialectic

"It would grieve one to the heart to hear what excellent doctrine some ministers have in hand, while yet they let it die in their hands for want of close and lively application." — Richard Baxter

Church pews are full of people who "know" the central tenants of the Christian faith, and yet sadly remain unchanged by them. There are also people in the pews that sincerely love the doctrines of the Christian faith but remain perpetually unsure of their practical relation to daily life. The Puritans were keenly aware of both of these phenomena. Consequently, the Puritans labored to bring the text of Scripture to bear upon the conscience of each listener. They worked hard to be practical, realizing that "doctrine is lifeless unless a person can 'build bridges' from biblical truth to everyday living."[6] Thus Thomas Hooker could write, "When we read only of doctrines these may reach the understanding, but when we read or hear of examples, human affection doth as it were represent to us the case as our own."[7]

To achieve practical preaching, the Puritans made much of application.[8] And such application was anything but narrow. As Ryken summarizes, there are seven categories of application to be found in Perkins’ Art of Prophesying:

- Those who are both ignorant and unteachable

- Those who are teachable, but ignorant

- Those who have knowledge, but are not yet humbled

- Those who are humbled

- Those who believe

- Those who have fallen away

- Those who are “mingled”[9]

Perkins' application matrix did not stop there; he also devised six types of application to all seven types of listeners in any one sermon. Taken to its full extent, every doctrinal statement of the sermon would require forty-two distinct applications in order to make application to every class of listener. This was, of course, not possible. But according to Packer,

“…anyone making an inventory of Puritan sermons will soon find examples of all forty-two specific applications, often developed with very great rhetorical and moral force. Strength of application was, from one standpoint, the most striking feature of Puritan preaching, and it is arguable that the theory of discriminating application is the most valuable legacy that Puritan preachers have left to those who would preach the Bible and its gospel effectively today.”[10]

It is clear that Puritan preachers were not content with the bare relaying of facts and information. Instead, their preaching was oriented toward specific goals and the best way to accomplish this, in their mind, was to strike at the center of the listener's conscience. What better way to accomplish this than through personal application of the text? According to Beeke, "Applicatory preaching is the process of riveting truth so powerfully in people that they cannot help but see how they must change and how they can be empowered to do so."[11] This type of preaching, as one might expect, was inherently confrontational without being cruel. Applicatory preaching is not "safe" preaching, for it involves meddling with the minds and wills of men. Beeke illustrates this well:

“…applicatory preaching is often costly preaching. As has often been said, when John the Baptist preached generally, Herod heard him gladly. But when John applied his preaching particularly, he lost his head. Both internally in a preacher's own conscience, as well as in the consciences of his people, a fearless application of God's truth will cost a price.”[12]

God, we suspect, would have it no other way.

Discriminatory Dialectic

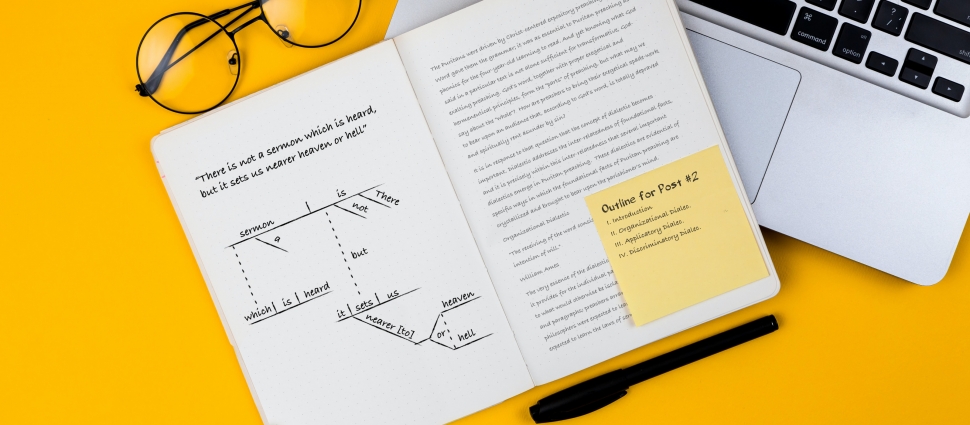

"There is not a sermon which is heard, but it sets us nearer heaven or hell." — John Preston

When children are learning to spell, errors are legion. One soon discovers that need for a dictionary to discriminate between what is correct and true and what is faulty and false. Gospel preaching plays a similar role. Once all the data of Scripture has been assembled for a particular text, the Puritan preacher was aware that the conclusion of that data would necessarily provoke distinctions among his audience. Truth, by definition, is exclusive, and therefore any pulpit proclamation of the truth would divide the hearers in some way. To the Puritan mind, this division was both unavoidable and absolutely necessary.

Puritan preaching was preeminently bent toward the producing and sustaining of the new birth. Such a purpose obviously presupposed that some men were yet spiritually dead. A common theme in Puritan preaching, therefore, was the elucidation of a dividing line between the saved and the lost. If what the Bible says is true, then preachers were under necessary compulsion to draw such a line in nearly every sermon.[13] More than that, they needed to know how to influence those on either side of the line. Joseph Hall put it this way,

"The minister must discern between his sheep and wolves; in his sheep, between the sound and the unsound; in the unsound, between the weak and the tainted; in the tainted, between the nature, qualities, and degrees of the disease and infection; and to all these he must know to administer a word in season."[14]

Discriminatory preaching, says Beeke, "clearly defines the difference between a Christian and a non-Christian, opening the kingdom of heaven to one and closing it against the other."[15]

The Puritan preachers did not follow this discriminatory model of preaching because it was in-style; they followed it because they saw it in the Bible. In the Puritan mind, Jesus was the greatest of the discriminatory preachers. His sermon on the mount was the magnum opus of pulpit discrimination. Puritan preachers understood that granting a false security to spiritual hypocrites was the most destructive of spiritual medicines. Far better to clearly open and apply the truth, and—as we will see next time—to do so in a way that is spiritual, simple, and sincere.

Joe Steele is Senior Pastor at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Huntsville, AL. He is husband to Elizabeth and father of four.

Related Links

"Preaching the Person and Work of Christ" by Ben Franks

"Puritan Preachers: William Perkins" by Joel Beeke

"Always Preach Christ?" by Ryan McGraw

Reformed Preaching by Joel Beeke

Why Johnny Can't Preach by T. David Gordon

Notes

[1] Cited in Ryken, Wordly Saints: The Puritans as They Really Were (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), 100.

[2] Ryken, 100.

[3] Ryken, 101.

[4] Quote from Percy Miller in Ryken, 100.

[5] J. I. Packer, A Quest for Godliness: The Puritan Vision of the Christian Life (Wheaton: Crossway Books, 1990), 281.

[6] Ryken, 101.

[7] Quoted in Ryken, 101.

[8] Reference Beeke, Living for God's Glory, 261 for an expanded discussion of the six types of application, according to the Westminster Divines:

(1) Instruction—doctrinal instruction;

(2) Confutation—refuting error;

(3) Exhortation—pressing obedience;

(4) Dehortation—rebuking sin;

(5) Comfort—encouraging perseverance; and

(6) Trial—proper responses to suffering.

[9] Ryken, 102.

[10] Packer, 288.

[11] Beeke, 259.

[12] Beeke, 261-262.

[13] See Mariano Di Gangi's, Great Themes in Puritan Preaching (Ontario: Joshua Press, 2007) for a compelling sermon on the importance and implication of the new birth, pp. 55-60.

[14] Quoted in Beeke, Living for God's Glory, 265.

[15] Ibid., 262.

Note: This post was originally published in August 2010.