William Ames: Saving Faith and Theology

Theology is the doctrine of living to God. More specifically, we live to God, through Christ, by the Holy Spirit. How we define theology determines how we study theology. If theology is merely the science of God, in which we study biblical data in order to talk about God, then open Bibles, clear thinking, and helps from church history are enough to get us going. However, if theology is about knowing the right God in the right way, and about making him known to others, then an accurate scientific system of doctrine is a necessary, but not a sufficient cause of true theology. The true theologian needs the Holy Spirit in his or her heart and saving faith to lay hold of God in Christ. We need a receptive tool to receive the theology taught in the Bible and to receive the God of the Bible through it.

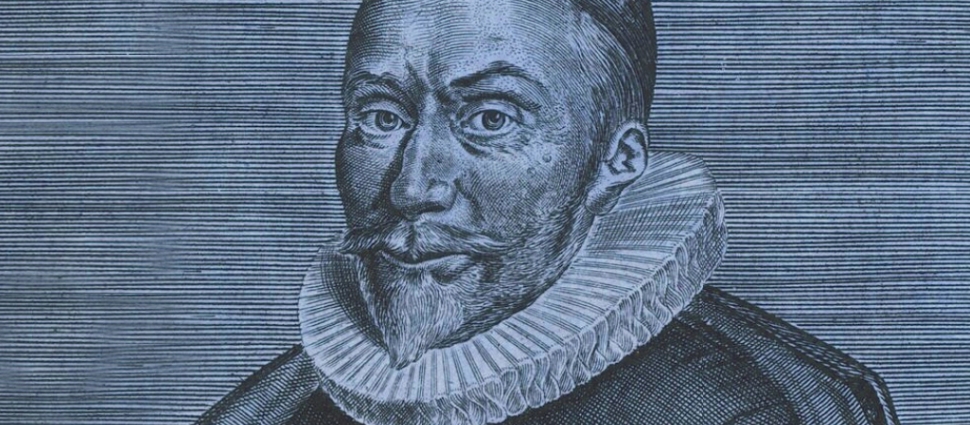

This led some Reformed theologians to treat the nature of faith before jumping into the doctrine of God and the rest of the system of theology. William Ames (1576-1633) is a preeminent example of doing this, and his Marrow of Theology became a standard text in England, New England, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. Later authors, like Peter van Mastricht, followed Ames’s example by placing saving faith at the outset of their systems, while the Westminster Confession and Catechisms brought in the topic to introduce the application of redemption. Faith fits well in both places, because faith in Christ is necessary to be a Christian as well as to study theology rightly. Ames’ treatment of saving faith shows us why faith is fundamental to studying theology.

Ames was not concerned with a generic faith in Scripture, let alone with a faith that is temporary or historical only, but with saving faith through which we come to know God. He defined faith as, “the resting of the heart on God, the author of life and eternal salvation, so that we may be saved from all evil through him and may follow all good (William Ames, The Marrow of Theology, Eusden translation, 80; citing Is. 10:20, Ps. 37:5, and Jer. 17:7). Faith is an act of understanding, but it goes beyond this and affects the will as well. Its fundamental meaning is receptive (citing Jn. 1:12): “It is an act of the whole man – which is by no means a mere act of the intellect” (80). While the knowledge involved in faith is common among those who are saved and those who are not, the will, depending on this knowledge, lays hold of God in faith. The nature of faith is to receive divine testimony and to commit oneself wholly to God through it (81). This point is a summary of why we need saving faith prior to studying the system of doctrine taught in Scripture.

Questions arose in the seventeenth-century over the nature of saving faith, especially its relation to the doctrine of the assurance of salvation. Calvin and others taught that assurance was of the essence of faith because it rests on divine testimony, though this faith could be strong or weak in believers. The Westminster Confession of Faith, while not denying this point, stated, “This infallible assurance does not so belong to the essence of faith, but that a true believer may wait long, and conflict with many difficulties, before he be partaker of it” (WCF 18.3). Their point was that it was possible to have an assurance of faith that would not fail us, while recognizing that the experience of this assurance fluctuates. The rest of the paragraph gives counsel how to foster assurance of faith, with the Spirit’s help, through using means. Earlier and later representatives of the Reformed tradition are basically in harmony, since all agreed that faith must be certain in its object, even though it could be stronger or weaker in its subject.

Ames treated this question with beautiful brevity and simplicity. He noted the infallibility of the object of faith while acknowledging the imperfection in the human subjects exercising faith. His statement is worth citing in full:

Faith is not more uncertain and doubtful because it leans on testimony alone, but rather more certain than any human knowledge because of its nature. This is so because it is brought to its object on the formal basis of infallibility – yet because of imperfection in the inclination [habitus] from which faith flows, the assent of faith often appears weaker in this person or that person than the assent of knowledge (81).

It is the object that gives certainty to faith, especially as it relates to what we believe, rather than the believing subject. God is the proper object of faith as we “live well by him” (citing 1 Tim. 4:10). Christ is the mediate object, rather than the ultimate object, of faith because “we believe through Christ in God” (81; citing Rom. 6:11, 2 Cor. 3:4, and 1 Pet. 1:21). Scripture exhibits, or sets before us, God in Christ as the object of faith. Ultimately, our faith must rest in God rather than man, which drives us back to divine testimony, through which we receive strength from God to pursue that which is truly good. While the exercise of faith in us may be strong or weak, the object of faith is always mighty to save. This is why true faith, even if it is weak faith, always saves.

Because the heart rests on God through faith and because God in Christ is the proper object of faith, God’s authority “is the immediate ground of all truth to be believed in this way” (81). Faith depends on divine authority through divine revelation alone (citing 2 Pet. 1:20-21 and Jn. 9:29). Yet the act of believing in God depends ultimately on “the operation and inner persuasion of the Holy Spirit” (81; citing 1 Cor. 12:3). This simultaneously unites the faith that we believe with the faith by which we believe, and it makes Ames’ treatment of the object and act of saving faith fully trinitarian. This faith is “true and proper trust,” without entailing “a certain absolute confidence of future good” (82). Faith can refer generically to trust in anyone or anything, even if fruitless or groundless, though our concern should be genuine trust in God. This brought him back to his definition of faith: “To believe in God, therefore, is to cling to God by believing, to lean on God, to rest in God as our all-sufficient life and salvation” (82). The general assent of the “Papists” is false because it does not bring life. Our “special assent” that God is our God in Christ, however, is not the first act of faith, but it flows from faith. This is because faith unites us to God in Christ and we must first be united to him by faith before we can be assured of the fact. Faith rests on God’s authority in divine revelation, but it must take us through divine revelation to God himself.

This leads to the last matter, which is having and exercising faith. Ames wrote, “Faith is the first act of our whole life whereby we live to God in Christ” (82), which is why it comes early in the theological system as well. We must surrender ourselves to God in Christ “as a sufficient and faithful Savior” (82). When the Scriptures link faith to assent, trust is always included. Trust in God is both the essence of faith and the fruit of faith as we continue to receive Christ, who offers himself to us “in the present” (82). He concluded, “The firm assent to the promises of the gospel is called both faith and trust, partly because, as general assent, it produces faith, partly because as a special and firm assent, it flows from trust as it takes actual possession of grace already received” (83). Though “certainty of understanding” may be lacking at times, believers may yet have “true faith hidden in their hearts” (83).

Ames’ description of faith is somewhat circular on purpose. Faith includes trust and it produces trust. The whole Christian life is exercising trust in the God who has revealed himself as the object of faith in Christ through his Word. The Spirit enables this trust in God through Christ. If theology is the doctrine of living to God, then faith is the instrument by which we must live to God. Theological studies may increase knowledge, but without saving faith they will not produce true theology. Ames reminds us that how we begin studying theology determines where we go in our studies and whether or not we grasp the goal of studying theology. Faith is the receptive instrument of salvation and the instrument of becoming a true theologian.