A Beautiful Picture of a Beautiful God

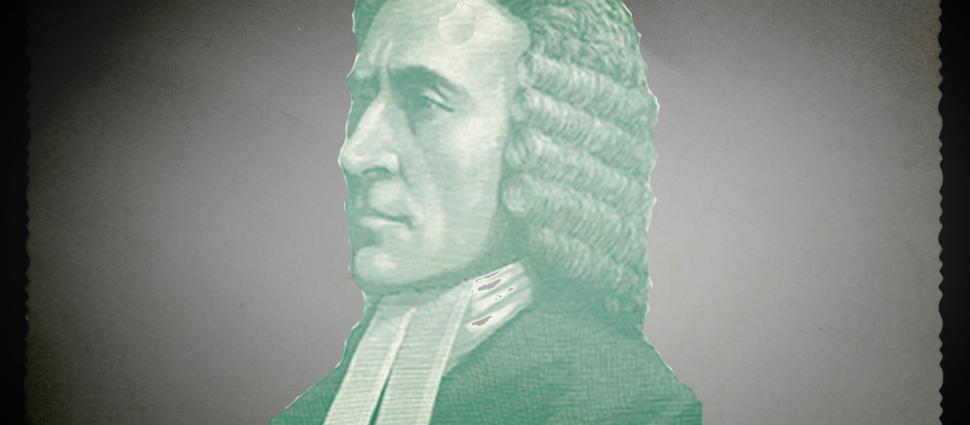

Dane C. Ortlund. Edwards on the Christian Life: Alive to the Beauty of God. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014. 207 pp.

There have been moments when my faith, my understanding of Christianity (the paradigm out of which I operated) changed fundamentally. One of those moments occurred in my second year in seminary, while sitting in our student center one brisk Jackson, MS morning listening to two of my fellow classmates lament the "dearth of biblical-theological instruction versus an overabundance of Systematic Theology at our institution." As a recovering dispensationalist who only knew Systematic Theology, I had absolutely no idea what they were talking about! This began my quest to discover this thing called "Biblical Theology." Once I was exposed to a redemptive-historical understanding of Scripture (i.e. as God's one story of restoring Eden through the Redeemer) I could not go back.

Then there was the time, about a year later, that I was struggling through Bahnsen's book on Van Til's Apologetic, laboring over yet another multipage explanatory footnote, feeling lost, stupid, and in a fog. Without warning, the concept of a presuppositional apologetic just "clicked," and suddenly there was no going back. That paradigm took over in my mind.

Now, thanks to Dr. Dane Ortlund's Edwards on the Christian Life, I have experienced yet another paradigm altering realization. I knew just a little about Edwards, but Ortlund's book opened up an entirely new appreciation for early America's great theologian. Ortlund's profound treatment of Edwards is summed up in the rather simple subtitle "Alive to the Beauty of God." Through this book I was awakened more to the beauty of God. Therefore, here are some brief, meager thoughts on the book that I offer unapologetically as a fan. In the spirit of wishing to make you a fan as well, I want to emphasize three things about Ortlund's book: First, this book will lead you into worship as you read it. Second, although this book is about Jonathan Edwards' view of the Christian life, it does not focus on the man as much as it guides us into a deeper appreciation for our Triune God through Edwards. Third, Ortlund's critiques of Edwards are surprisingly poignant to the foibles we see in our own lives and churches today.

Worship while Reading

Ortlund tantalizes the reader to worship God from the very beginning. In only the second paragraph he sums up 1500 years of providential Christian thought in an amazing eight sentences, and then caps it off with his summary of Edwards' legacy: "sinners are beautified as they behold the beauty of God in Jesus Christ" (p.24). He then goes on to explain Edwards' concept of beauty as a moral category of God himself, encompassing both God's excellency and his holiness. Ortlund immediately applies this concept to the reader, challenging us not to see our personal holiness as something unpleasant or boring, but rather actually appropriating the beauty of our Creator. Edwards would have us see that, "in truth there is nothing more thrilling, more solid, more exhilarating, more humanity restoring, more radiantly joyous, than holiness" (p. 26). For Edwards the idea that God is beautiful, that many of his more appealing attributes can be assumed under the description of "beauty," means that in redemption God wants to make us beautiful as well. If God's joy, God's happiness, God's holiness are all part of his beauty, then that means he makes Christians beautiful by giving us joy, happiness, and holiness.

To make his case about the beauty of God, Ortlund sites a sermon of Edwards on James 1:17 which was so beautiful I had to stop reading, wipe the tears from my eyes, and sit in meditative silence as the concept of the beautiful holiness of God washed over me. I'll not quote it here; you need to experience it in context. The first chapter is worthy of its own review as in it Ortlund inundates the reader with Edwards' compelling descriptions of God's beauty such as, "the gospel above all else is where God's beauty is beheld" (p.28), and the thought that "to be a Christian is to be a little, frail, finite, morally faltering picture of the beauty of God" (p.30). Repeatedly throughout the first chapter I had to stop reading because I was overwhelmed by Edwards' understanding of the beauty of God. This first chapter alone is worth the price of the book, and if you read nothing else read this chapter as a personal devotion. It will lead you into worship.

Appreciating the Trinity in the Christian Life

Ortlund's presentation of Edwards not only leads into worship, but throughout the rest of the book the reader will grow in appreciation for the work of the Trinity. Edwards 'beautifies' the concept of new birth, teaching that regeneration is the decisive act of beauty in the Christian's life so that "they are made partakers of God's fullness, that is, of God's spiritual beauty and happiness" (p.43). Edwards uses the concept of love itself as proof of the Trinity, saying that when 1 John teaches "God is love," it means, "there are more persons than one in the Deity: for it shows love to be essential and necessary to the Deity, so that his nature consists in it" (p.56). In this love of God, the Christian experiences the joy of "resting satisfied in God, in his beauty and love" (p.76). Referring back to the love of the Trinity, Edwards says "he who has divine love in him has a wellspring of true happiness that he carries about in his own breast" (p.76). For Edwards, the key to this wellspring of happiness is in the Bible.

Edwards believed that "Scripture is God's tool of human beautification" (p.103) and that "God gave his word for the sake of men, for their happiness" (p.111). Even prayer, for Edwards, finds its foundation in the beauty of God and the work of the Trinity. For Edwards, "what we are given in regeneration is the third person of the Trinity" (p.116), which means that prayer is "God the Holy Spirit bringing us to commune with God the Father through God the Son" (p.117). Such a description leads Ortlund to conclude that Edwards "paints a portrait of God so lovely, so delightful, so eager to commune with us and beautify us through the Holy Spirit, that we are drawn up into prayer almost before we realize what is happening" (p.117).

Ortlund continues by commending Edwards' application of beauty to the pilgrimage metaphor of the Christian life, reminding us that as "our hearts slide away from the enjoyment of God, and toward enjoyment of this world... we slowly transition from being pilgrims through this world to being citizens of this world" (p.132). Into that inevitable slide, Edwards shines the beauty of God, "to go to heaven, fully to enjoy God, is infinitely better than the most pleasant accommodations here... these are but shadows; but God is the substance... it becomes us to spend this life only as a journey towards heaven" (p.132). After the 'beautifying' the pilgrimage metaphor, Ortlund treats the reader to Edward's view of how Christian obedience demands a robust sense of the beauty of God. That is, we must love God in order to obey him since "the will only chooses what the heart loves" (p.135). Obedience, for Edwards, comes from a heart that loves our beautiful God so much that the will longs to choose the beautiful.

Long before Tim Keller popularized Ed Clowney's "three ways to live" interpretation of the parable of the Prodigal Son, which was based on C.S. Lewis' essay "Three Kinds of Men," Ortlund shows that Edwards taught the same thing in The Nature of True Virtue. Ortlund explains, "real obedience is living out of a new sense of the heart, in which God and holiness now appear beautiful rather than ugly... anyone can behave in a morally upright way out of self-love, but true virtue behaves a certain way out of a heart that is drawn to God and his beauty" (p.137). Or to put it another way, "if we truly believe that Christ is our greatest treasure, and sin our greatest danger, and God the loveliest beauty, then we will live a certain way... the obedience of our hands reflects the doctrine of our hearts" (p.140). Edwards presents the beauty of the Trinity as the motivation for Christian obedience--what a glorious thought! Edwards continues to lead us into glorious thoughts and a deeper appreciation for the Trinity as he applies God's beauty to our concepts of Satan, the soul, and heaven itself.

Poignant & Applicable Critique

While the entire book was a worthwhile read, I was surprised by the last chapter in which Ortlund turns from fan and advocate for Edwards to a reluctant-yet-poignant critic, even applying Edwards' oversights to foibles we see in the church today. He has four criticisms of Edwards, but the focus of the chapter is on the question of "whether Edwards sufficiently brought the gospel to bear on the hearts of his people" (p.177), which he answers "with a carefully qualified 'No!'" (p.179). Ortlund is quick to clarify that Edwards understood and was faithful to preach the gospel, but it was "not the dominant theme in his theology of the Christian life" (p.179). In a summary that many contemporary pastors ought to read, Ortlund says, "Edwards did not have well-developed gospel instincts when it came to bringing his sermons home to his people. For all that he said about the beauty of Christ, he could have been clearer on what precisely it is that makes Christ so beautiful—namely, his grace toward sinners, including regenerate sinners" (p.180). Edwards had no doubt that the gospel was good news for unredeemed sinners, and his relentless application of the gospel to the unredeemed was a major factor in the Great Awakening. However, the gospel is about more than getting "saved." The gospel is not merely about how a sinner gains entrance into God's Kingdom, but it is also good news for redeemed sinners seeking to live faithfully and joyfully in God's Kingdom. Christians are to look to the truth of the gospel and the power of the Spirit for their post-conversion struggles against sin. Edwards missed such an application to his flock. My fellow pastors, let us be humbled that a theologian of Edwards' caliber could have such a blind spot, and let us endeavor not to add it to our growing list of blind spots.

In addition to this lack of gospel-centered preaching, Ortlund points out that while Edwards was clearly in tune with his interior life and heart motivations, he failed to apply the gospel to the heart-struggles of the regenerate. Specifically, Edwards went beyond healthy self-examination "into an unhealthy preoccupation with his own spiritual state, encouraging the same preoccupation among his people" (p.181). Ortlund points out a remarkable example when Edwards states, "'tis not God's design that men should obtain assurance in any other way, than by mortifying corruption, and increasing in grace, and obtaining the lively exercises of it" (p.182). It is remarkable that the theologian of God's beauty would seek to anchor assurance not in the beauty of God revealed in the Gospel of Jesus Christ, but in the believers' activity of resisting and killing sin! While such activity is a part of sanctification, it is by no means the basis of assurance. Rather, it is the finished work of Christ on the cross and empty tomb to which we look for assurance. As Ortlund clarifies, "we kill sin and gain assurance of God's favor fundamentally by enjoying the truth that Christ was killed for sin and lost God's favor on the cross" (p.182).

Edwards was prone to this interior focus because of his preoccupation with the subjective experience rather than focusing on the objective realities of the gospel. To bring this point home, Ortlund contrasts diary entries of Edwards to his friend and missionary David Brainerd. Both of them, at about the same age, struggled with whether or not God really loved them. The comparison provides a stark example of a gospel focus versus an experience focus. Orltund notes, "Edwards questioned the state of his soul and turned to the intensity and sequence of his own experience. Brainerd questioned the state of his soul and turned to the comfort of imputation—Christ's righteousness was his" (p.183). As I read this section, I could not help but wonder if the rise in popularity of Edwards in the contemporary Reformed world—and the associated focus on the interior life with him—has led to the current sanctification debate. Could it be that one side overemphasizes the subjective appreciation of the imputation of Christ's righteousness to deliver us from the guilt of sin while the other side fixates on the objective appropriation of Christ's righteousness to deliver us from the power of sin? Perhaps, but that is topic for another day!

Ortlund finishes up his treatment of Edwards by critiquing his view of creation, his use of Scripture, and his doctrine of anthropology. In all these, Ortlund brings a keen mind and a theologian's care to the material. He does not want the Christians reading this book to be so enamored with Edwards' view of the beauty of God that they follow him into his mistakes. Ortlund does not merely want the reader to understand Edwards; Ortlund wants Christians to live in the robust beauty of God that Edwards declared, even if he wasn't always consistent in the application of that beauty.

After reading this book, I found myself burdened with the responsibility to provide a glimpse of the radiant beauty of God in the gospel to the Christians under my care, while at the same time overjoyed that "the fundamental calling of leaders of God's people is not only to be undershepherds of the chief Shepherd but also under-beautifers of the chief Beautifier" (p.32). If you are a leader of any sort in the church, buy and consume this book. If you feel a stagnation in your Christian life, read this book. If all you know of Edwards is the slanderously out-of-context excerpt from "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" in your high school literature class, read this book! Dane Ortlund has done the church a great service by giving us an accessible portrait of Edwards and the beautiful God he adored. Take up and read!

Sean Sawyers is the senior pastor of Trinity PCA in Orangeburg, South Carolina, husband to Nikki, father of five, does not have a blog but you can friend him on Facebook.