A Mountain Range Christmas

As we head toward another Christmas--and a renewed time of remembrance of the fulfillment of the prophecies that God gave for millennia concerning the Christ--it would do us good to step back and consider the fact that the Old Testament prophecies about Christ were often not time-specific, neatly packaged prophecies--but mountain-ranges of prophecy about all that the Savior would be and do in both His first and second coming. Our minds often turn, at this time of year, to the prophecies concerning the virgin that would conceive and bear a Son whose name would be Emmanuel (Is. 7:14), of the child who would be born whose name would be Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Princes of Peace (Is. 9:6) and of the fact that One who would be ruler over Israel--who would be from everlasting--would be born in the little town of Bethlehem (Micah 5:2). We love to look back with delight as we see the way in which these prophecies, given so long before God fulfilled them, were so specifically and clearly fulfilled in the birth of Jesus. However, we often forget that the Old Testament spoke of another dimension of the advent of the Christ. The entire Old Testament pointed forward to the coming Savior--who, in His work on the cross and in His return to judge the world in righteousness--would bring about, in the consummation, the salvation and judgment of all men.

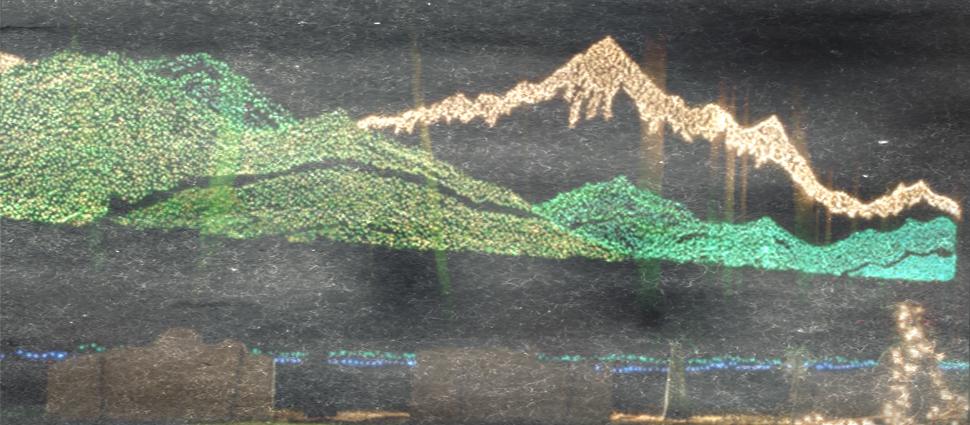

Louis Berkhof, in his book Principles of Biblical Interpretation, illustratively explained how it is that the prophecies made about Christ in the pages of the Old Testament appear more like mountain ranges than mountain tops. He wrote:

The element of time is a rather negligible character in the prophets. While designations of time are not wanting altogether, their number is exceptionally small. The prophets compressed great events into a brief space of time, brought momentous movements close together in a temporal sense, and took them in at a single glance. This is called 'the prophetic perspective," or as Delitzsch calls it "the foreshortening of the prophet's horizon." They looked upon the future as the traveller does upon a mountain range in the distance. He fancies that one mountain-top rises up right behind the other, when in reality they are miles apart. Cf. the prophets respecting the Day of the Lord and the two-fold coming of Christ.1

We see how this is played out in the way in which the elderly Simeon spoke of the destiny of the baby Jesus. "This child," he said, "is destined for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign which will be spoken against (yes, a sword will pierce through your own soul also), that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed" (Luke 2:34-35). Simeon was tying together all that the Old Testament was saying about the work of Jesus in both His first and second coming. This is how Jesus could speak about events that were centered on His second coming--typified by events in His first (i.e. in the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70)--and the disciples thought that they would all be fulfilled in their lifetime (Matt. 24).

John the Baptist struggled to come to terms with this as well. Having pointed to Jesus while making that grand declaration, "Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world," John seems to have doubted whether Jesus really was the long awaited Redeemer. When he was in prison, John sent messengers to Jesus to ask Him, "Are you the coming One are do we look for another" (Matt. 11:3)? What accounted for this stumbling in doubt after making such a bold and accurate pronouncement about Jesus? John was reflecting on what the Old Testament said about the Redeemer coming to judge. John, remember, proclaimed, not just that Jesus was "the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world," but also that "His winnowing fan is in His hand, and He will thoroughly clean out His threshing floor, and gather the wheat into His barn; but the chaff He will burn with unquenchable fire" (Luke 3:17). John expected the judgment of the nations--not simply the salvation of people--in the first coming of Christ. John was looking at the mountain range of Old Testament prophecy about Christ. Our Lord's gracious response to one who had served Him so faithfully was an appeal to one particular prophecy in Isaiah. "Go and tell John the things which you see and hear: The blind see and the lame walk; the lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear; the dead are raised up and the poor have the gospel preached to them. And blessed is he who is not offended because of Me.” Jesus was, of course, pointing out that the gracious healings that He was performing bore witness to the Messianic character of His Person and ministry. They were proofs--drawn from Isaiah 35:5-6--that He was indeed the Christ. The appeal to Isaiah did not set aside the other mountain tops of prophecy about His work of judgment--it was merely the Savior pointing out the first set of mountains in the mountain range of prophecy about Him.

If John the Baptist's error was to want to stand back and look at the mountain range rather than at the contours of the mountain tops, it is safe to say that ours is the opposite error. We have difficulty holding together the gracious character of Jesus' first appearance with the both gracious and wrathful character of His second. We tend to focus more on the first coming with its shouts of salvation rather than on the second with its promised shout of salvation and judgment. In a sense, we often wrongly separate the baby in the manger from the Lion on the throne. We have to learn to look at both the mountain tops and the mountain range. We do so by looking at the whole Christ in the whole of the Scriptures.

As we again enter in on a time of special meditation on the wonder of God manifest in the flesh--come a baby in the manger, let us also meditate on the promised return of God glorified in the flesh--coming as the Lion of the Tribe of Judah. Let us learn to search the Old Testament to see the mountain tops of prophecy about Christ, but let us do so recognizing the mountain range of which it is a part. Let us celebrate all that the baby in Bethlehem means concerning the promised salvation and judgment of the world. It is all united in the One eternal and everlasting Christ--the just God and Savior.

1. Louis Berkhof Principles of Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1952) p. 150