Anglican Thomas Watson’s Evening Sermon

Nov 18, 2016

Having therefore these promises, dearly beloved, let us cleanse ourselves. (2 Corinthians 7.1 KJV)

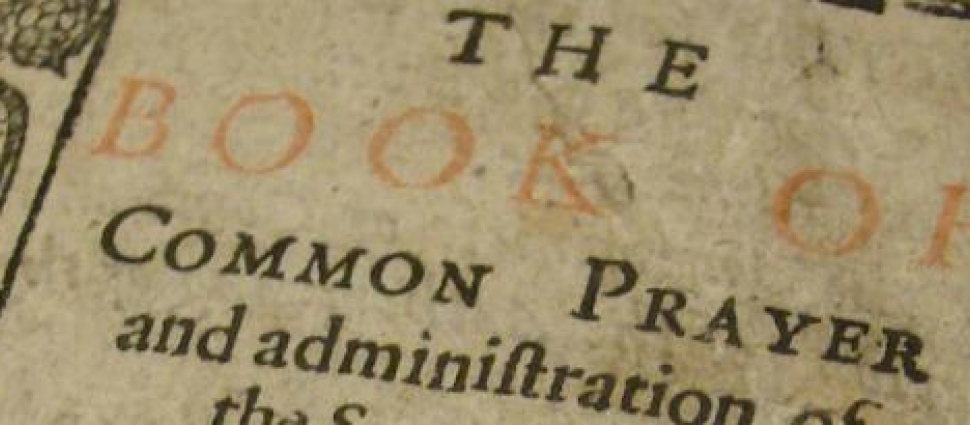

We are at the last of the works by Anglican Thomas Watson in our reading of the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. “The Great Ejection” was the explusion of nearly 2,000 Anglican ministers from their cures in the 1662 Act of Uniformity. The final work is the transciption of Watson’s evening sermon preached on his final Sunday as pastor of St. Stephen’s, Walbrook. These are his last words to the congregation and in it he gives a moving summary of the nature of pastoral ministry.

Watson returns to the triple pattern of Anglican preaching in an exegesis of the title, “dearly beloved”, the meaning of the exhortation, “Let us cleanse ourselves”, and the application how his hearers should be cleansed and sanctified, “having these promises.”

Taking the Apostle Paul as his example under his first point, he walks his congrgation through Paul’s letters to pause at each point where Paul sets the depths of his love before them. Ministers employ the head and the heart, writes Watson, “His head with labor and his heart with love.” He insists that the depth of love that Paul writes is true in all godly ministers of Jesus Christ. They are full of sympathy and affection toward those over whom God has made them pastor, how very true! Why does such a love overflow like a spring? It is God’s grace. “Grace does not fire the heart with passion, but with compassion. Grace in the heart of a minister files off that ruggedness that is in his spirit, making him loving and courteous. Paul once breathed out persecution, but when grace came this bramble was turned to a spiritual vine, twisting himself about the souls of his people with loving embraces” (p. 162).

Watson explains the nature of God’s cleansing when he writes next of how God’s grace makes a man broken and builds him up again into His fit instrument, fit as an example of God’s mercy and fit as an instrument that exercises pastoral care in ardent love and affection because knotty and stubbon hearts among the congregation are softened by the fire of such love: “He is full of love, he exhorts, he comforts, he reproves, and all in love. He is never angry with his people except when they will not be saved. How loth is a minister of Christ to see precious souls like so many jewels cast over-board into the dead-sea of hell” (p. 163).

As Watson concludes he leaves his people twenty points of application in a metaphor of a last will and testament. The twentieth set the proper perspective of all he wrote of the loving pastor. I write this because some may read Watson’s description and think his outline of the pastor is mere hyperbole, spoken in the moment. In a time when so much is written of how pastors are to live almost defensively among his people in light of the hurt they receive, point twenty says it all. The extent to which a pastor ponders eternity, is his hidden resource.

Every day think upon eternity. Oh, eternity, eternity! All of us here are, ere long – it may be some of us within a few days or hours – to launch forth into the ocean of eternity. …The thoughts of eternity would make us very serious about our souls. …Oh how fervently would that man pray that thinks he is praying for eternity. Oh how accurately and circumspectly would that man live who thinks that upon this moment hangs eternity. …The thoughts of eternity would keep us from grieving overmuch at crosses and sufferings of the world. Our sufferings, says the apostle, are but for a while. What are all the sufferings we can undergo in th world in comparison with eternity? Affliction may be lasting, but it is not everlasting. Our sufferings are not to be compared to an eternal weight of glory (p. 177).