Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg – The First Protestant Missionary to India

Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg – The First Protestant Missionary to India

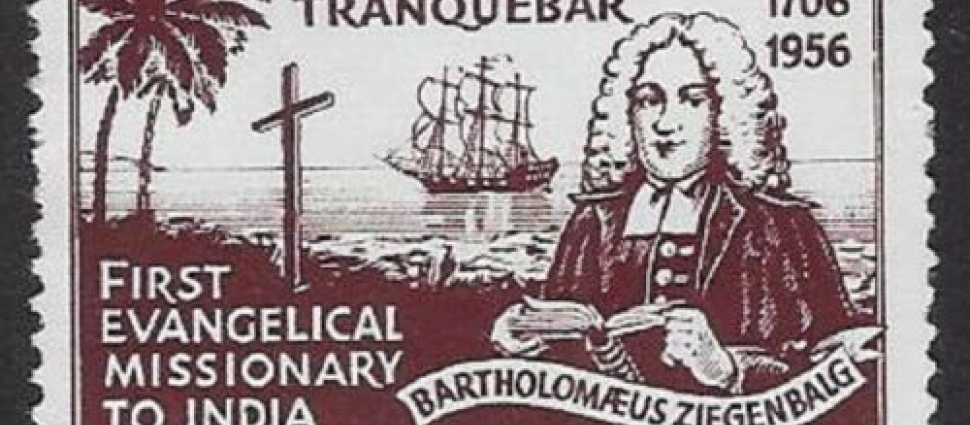

While William Carey’s role in the evangelization of India is undisputed, few remember a two-men team who preceded him by 88 years. In reality, the German Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Plütschau, who landed in the Indian region of Tranquebar in 1706, can be considered the first Protestant missionaries to India. Their endeavor is known as the Tranquebar Mission or the Danish-Halle Mission (since it was sponsored by the Danish king and the students and faculty of Halle University – especially theologian, A. H. Francke).

A Tamil Bible

Born in 1682 and 1676 respectively, Ziegenbalg and Plütschau were both Halle graduates– both known for their piety, devotion to the Scriptures, sacrificial love, and interest in education. Of the two, Ziegelbalg was the most linguistically talented. Within six months of his arrival at Tranquebar, he was able to read, write, and speak Tamil, a local language that was particularly difficult for Europeans to master.

In 1708, being fluent, he began translating the New Testament, finishing his first draft in two and a half years – an impressive record, if we consider he also fulfilled his pastoral and evangelical duties while troubled by ill health. He also translated Luther’s Catechism and several hymns and prayers, and started the Old Testament, going as far as the book of Ruth.

Far from being content with a wooden translation, Ziegelbalg spent time studying the nuances of the Tamil language as they appeared in their cultural context. He did so through conversations and through the study of Tamil classical literature, both on his own and in local schools.

He later described his cultural discoveries in two long ethnological treatises which became popular in Europe. These volumes, together with a Tamil grammar book for future missionaries, helped to launch the study and appreciation of Oriental languages and cultures in Germany and have been influential in dispelling the negative conceptions many Europeans had fostered about India.

Although he had brought his own printing press, he had to request the presence of two Dutch blacksmiths to create Tamil character molds. There was also a scarcity of paper. Most Tamil classics were written on palm leaves. He solved this problem by setting up a paper manufactory.

To Bring Many to Salvation

As most missionaries, he had times of discouragement. “If we consider the success of this Mission from its first beginning; it hath not yet indeed been answerable to our desires: the iniquity of the times, fewness of the laborers, the perverse lives of some Christians among us, the rudeness of the pagans, the dignity of the employment itself and our own insufficiency for it, the want still of more necessary helps, together with other impediments, have been the cause why this work has hitherto made no greater advances,”[1] he wrote, in Latin, in 1716 – at the end of a two-year visit to Europe, where he got married.

Were Scriptures true when they taught that His word never returns void? “The seed of the Word sown here and there would have seemed as dead to us, unless we had believed in hope even against hope that, after so many tempests and commotions, it would in time spring up and bring forth fruit abundantly. Almighty God, who is never wanting either to the planter or to the waterer, can give that increase to us, or to those who may come after us in this arduous affair, as it was hardly to be expected from so small beginnings.”[2]

He concluded the letter with a prayer that God would bring him back safely to India “and guide and prosper [his] endeavours of guiding many souls to salvation.”[3]

What he considered small advances, however, were impressive at a time when few Christians ventured to bring the gospel outside of Europe – in fact, so few believed in the expediency of missions that King Frederick IV of Denmark couldn’t find any candidates in his own country. Nine months after the start of the Danish-Hall Mission, nine Tamils were baptized. Five years later, the local church counted over 200 members.

Opposition

This progress was also impressive considering that, unlike the Jesuits missionaries who had arrived before him, Ziegenbalg was no respecter of castes. From his ethnological studies, he had concluded that the caste system was not simply a social arrangement, but was rooted in the Hindu religious system.

Although he allowed some customs related to castes to be kept in church (for example, regarding seating), he insisted in equality in Christ for all members. This won him some enemies, as some high-caste Tamils refused to join a church where they had to be in equal standing with low-caste members. At least one group plotted to kill him. But this opposition was rare, and most locals were interested in his message.

Both Ziegenbalg and Plütschau were also temporarily arrested, each on a separate occasion, by the Danish government, when their intervention in civic causes was considered inappropriate. In each case, the charge was encouraging rebellion.

Preparing Pastors and Evangelists

As many pastors at that time, Ziegenbalg focused on education, and opened cross-caste schools for boys and girls, reassuring hesitant parents that Tamil classics would be taught alongside the Bible. Of the first Tamils to be appointed as catechists, eight were from the first class of Ziegenbalg’s students.

After returning to India in 1716, Ziegenbalg founded a seminary to train Tamil pastors and catechists. Catechists gave theological instruction, provided pastoral care to church members, tended to the sick, and evangelized the area. Both men and women were eligible to become catechists. Eventually, there were four or five Tamil catechists for every European missionary.

Ziegenbalg died in 1719 at 36 years of age, but his legacy continued. In fact, he is considered one of the most influential missionaries in Christian history. His emphasis on Bible translation, cultural sensitivity, and establishment of an indigenous church - still a novelty at that time - provided a model for many to follow, so much that historian Daniel Jeyaraj calls him “the father of modern Protestant mission.” After Ziegenbalg’s death, the German linguist and missionary Johann Philipp Fabricius continued his work of translation.

While most churches in the west might have forgotten Ziegenbalg’s name, it is still well-known in India, particularly in the state Tamil Nadu. In 2006, three hundred years after Ziegenbalg first landed in India, the state promoted a week of festivities and issued a stamp in his honor. As it often happens in the case of early missionaries, these festivities were attended by people of all religions. While not all Tamils share the same joy in the souls Ziegenbalg led to Christ, they are grateful for Ziegenbalg’s contribution to the development of their language and culture. In fact, even from a historical point of view, Ziegenbalg’s writings – being the fruit of his own personal involvement in the lives of the people – are still one of the best sources for the study of South Indian history and traditions.

[1] Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg, Propagation of the Gospel in the East: Being a Collection of Letters from the Protestant Missionaries and other worthy persons in the East-Indies, etc., vol. 3, London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1718, 228-229

[2] Ibid., 219

[3] Ibid, 230