Christ, Fully-Human

There is a Christological impoverishment in the evangelical world. Christians, by and large, excel at embracing the divine nature of Christ. And yet the confusion comes when Christians are forced to reflect carefully upon the true human nature of Christ. A study of orthodox Christology would help clear away this confusion, and help us embrace and appreciate of the humanity of Christ.

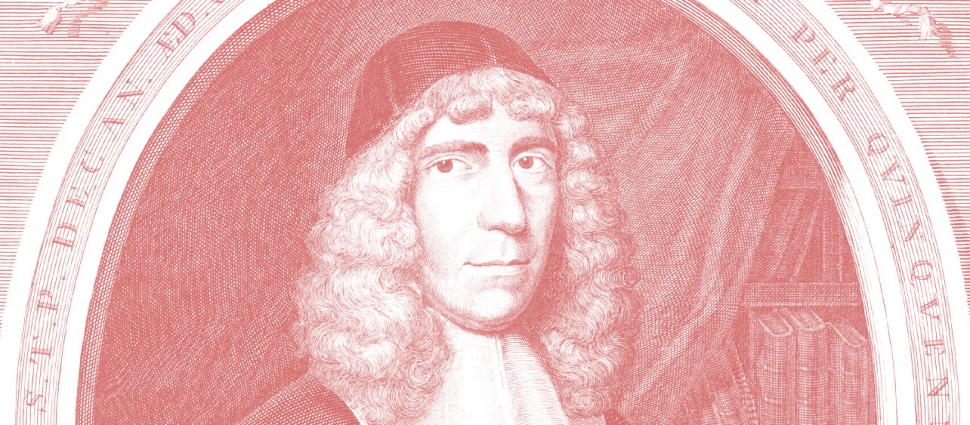

Perhaps no writer that I can think of embodies that rich Christological legacy as well as John Owen. We see this most clearly in volume 3 of Owen’s collected Works, where he enumerates the work of the Spirit in the life and ministry of Jesus. And so I'd like to offer a precis of what Owen says.

Owen begins by acknowledging that the Holy Spirit’s first role in the ministry of Jesus was the creation of Christ’s physical body in the womb of Mary (Luke 1:35). Owen also goes further by reminding the reader that the Spirit empowered the whole life, work, and ministry of Christ as well.

Owen makes it clear that Christ’s human nature was “in the instant of its conception sanctified and filled with grace by the Holy Spirit.” He then says that the Spirit "carried on that work whose foundation he had thus laid” (3:168). Owen argues that the life and ministry of Jesus was as a man, not as a super man. He was a true man with a true body and a reasonable soul. As Owen enumerates the work of the Holy Spirit in the life and ministry of the person of Christ, he relies upon thoroughly orthodox theology.

Owen next makes two lengthy comments on this point that are deeply instructive as to the relationship of the divine and human natures of Jesus when it comes to his public ministry and his soul. First, Owen says, “The Lord Jesus Christ, as man, did and was to exercise all grace by the rational faculties and powers of his soul, his understanding, will, and affections; for he acted grace as a man, ‘made of a woman, made under the law.’ His divine nature was not unto him in the place of a soul” (3:169).

Note, as we follow along here, that Owen is explicitly refuting Apollinarian Christology. Apollinaris understood Christ as assuming a human body and soul, but not a human spirit. For Apollinaris and his followers (who saw a distinction between soul and spirit), Jesus had a human soul, but the divine nature took the place of the human spirit in the person of Christ. The effect of this theological move was to put the divine nature in the seat of Christ’s own self-consciousness and self-understanding. The result of this, of course, was a God-Man who was supposed to be like us “in every respect” (Heb. 2:17; 4:17) and yet very much lived with the divine nature in the driver’s seat, as it were.

It is also worth noting that this was explicitly condemned by Damasus at the Council of Constantinople in 381:

“We pronounce anathema against them who say that the Word of God is in the human flesh in lieu and place of the human rational and intellective soul. For, the Word of God is the Son Himself. Neither did He come in the flesh to replace, but rather to assume and preserve from sin and save the rational and intellective soul of man.”

To believe that the God-Man lived with a “divine self-consciousness” apart from special revelation is Apollinarian. Owen does not here develop a full theology of Christ’s knowledge. He does assert the importance of maintaining the full human soul of Christ and not intermingling his human mind or soul with the divine.

Evangelicals who are troubled today by the idea that the God-man might not possess an immediate and complete knowledge of some aspects of his person, his prior communion with the Father, or that he would have self-imposed limits upon his knowledge, would do well to meditate on whether the views of Apollinaris could be refuted by their own understanding of the nature of Christ. In what sense does Christ have a real, human, reasonable soul? Do we smuggle in an assumption that Christ actually has a divine soul? I suspect—though I could not conclusively prove it—that some evangelicals view Jesus as being a man, yet also still see Jesus as having a divine rather than a true human soul and mind.

Owen continues:

His divine nature was not unto him in the place of a soul, nor did immediately operate the things which he performed, as some of old vainly imagined [Apollinaris]; but being a perfect man, his rational soul was in him the immediate principle of all his moral operations, even as ours are in us. Now, in the improvement and exercise of these faculties and powers of his soul, he had and made a progress after the manner of other men; for he was made like unto us ‘in all things,’ yet without sin. In their increase, enlargement, and exercise, there was required a progression in grace also; and this he had continually by the Holy Ghost: Luke 2:40, ‘The child grew, and waxed strong in spirit.’ The first clause refers to his body, which grew and increased after the manner of other men; as verse 52, he ‘increased in stature’ The other respects the confirmation of the faculties of his mind,—he ‘waxed strong in spirit,’ So, verse 52, he is said to ‘increase in wisdom and stature.’ He was πληροὐμενος σοφίας, continually ‘filling and filled’ with new degrees ‘of wisdom,’ as to its exercise, according as the rational faculties of his mind were capable thereof; an increase in these things accompanied his years, verse 52. And what is here recorded by the evangelist contains a description of the accomplishment of the prophecy before mentioned, Isa. 11:1–3. And this growth in grace and wisdom was the peculiar work of the Holy Spirit; for as the faculties of his mind were enlarged by degrees and strengthened, so the Holy Spirit filled them up with grace for actual obedience (3:169, my emphasis).

Second, Owen proceeds further on this very important point relating to Christ and how he gained knowledge: “The human nature of Christ was capable of having new objects proposed to its mind and understanding, whereof before it had a simple nescience” (3:169-170). In other words, Jesus learned in a linear and finite fashion, just as all humans do. In fact, he says that anything more would cause him to differ from his fellow humans, which is unacceptable, since “that which Christ has not assumed he has not healed” as the Cappadocian fathers were clear on.

Owen considers the finitude of Christ’s mind to be a non-negotiable:

And this is an inseparable adjunct of human nature as such, as it is to be weary or hungry, and no vice or blamable defect. Some have made a great outcry about the ascribing of ignorance by some protestant divines unto the human soul of Christ…Take ‘ignorance’ for that which is a moral defect in any kind, or an unacquaintedness with that which any one ought to know, or is necessary unto him as to the perfection of his condition or his duty, and it is false that ever any of them ascribed it unto him. Take it merely for a nescience of some things, and there is no more in it but a denial of infinite omniscience,—nothing inconsistent with the highest holiness and purity of human nature. So the Lord Christ says of himself that he knew not the day and hour of the end of all things, [Mark 13:32]; and our apostle of him, that he ‘learned obedience by the things that he suffered,’ Heb. 5:8. In the representation, then, of things anew to the human nature of Christ, the wisdom and knowledge of it was objectively increased, and in new trials and temptations he experimentally learned the new exercise of grace. And this was the constant work of the Holy Spirit in the human nature of Christ. He dwelt in him in fulness; for he received him not by measure. And continually, upon all occasions, he gave out of his unsearchable treasures grace for exercise in all duties and instances of it. From hence was he habitually holy, and from hence did he exercise holiness entirely and universally in all things (3:170-1).

Owen’s point here is that it is no deficiency or fallibility in Jesus for him to have a finite knowledge, a finite mind, or a limited self-understanding. This is the way all humans live and operate. Not only that, but the text of Scripture demands such a conclusion.

This of course, leaves one to wonder: how did Jesus minister, then? If he has a human soul and body, what place does this leave for the divine in his human ministry? Well, Owen is quite clear, as is Scripture: He always has his full divine nature, and yet willingly lives without recourse to it; instead, it is the Holy Spirit who did these things through the person of Christ.

Intuitively we tend to assume that the miracles of Jesus were a direct result of Christ’s own divine nature. Owen’s answer becomes predictable by this point. “The Holy Spirit, in a peculiar manner, anointed him with all those extraordinary powers and gifts which were necessary for the exercise and discharging of his office on the earth” (3:171). Owen points to Isaiah 61:1 (cited in Luke 4:18-19) as proof of this, along with many other passages.

He goes further: “It was in an especial manner by the power of the Holy Spirit he wrought those great and miraculous works whereby his ministry was attested unto and confirmed. Hence it is said that God wrought miracles by him” (3:174). To argue this point Owen points to Acts 2:22, which notes that these miracles of Jesus “God did by him.” Then Owen notes that these miracles are “all immediate effects of divine power” (3:174).

If Jesus learned in a linear fashion, how did he know the things that he did know? Of course, the answer is not to look to Christ’s divine nature, which would fall back into the error of Apolinaris. Instead, the answer was that he knew, learned, and taught by the power of the Spirit. Owen notes that by the Spirit “[Christ was] guided, directed, comforted, supported, in the whole course of his ministry, temptations, obedience, and sufferings” (3:174). Luke 4:1 is an immediate text that Owen draws upon to make this point, where Jesus is “led by the Spirit into the wilderness.” It is not Jesus’ immediate intuition that leads him into the wilderness, but the Spirit. In Owen’s analysis, “he thus began his ministry in the power of the Spirit, so, having received him not by measure, he continually on all occasions put forth his wisdom, power, grace, and knowledge, to the astonishment of all, and the stopping of the mouths of his adversaries, shutting them up in their rage and unbelief” (3:174).

I suspect many Christians today would attribute these activities and graces of Christ to the divine nature of Jesus, not the Holy Spirit. Yet according to Owen, “His divine nature was not unto him in the place of a soul, nor did immediately operate the things which he performed” (3:169).

The point that Owen makes is that everything in the ministry of Jesus Christ that testified to his person was done by the Spirit. The Spirit was even with him in the end of his ministry. “By him was he directed, strengthened, and comforted, in his whole course,—in all his temptations, troubles, and sufferings, from first to last” (3:175).

I sense major confusion in the evangelical world on this subject. Some Christians may be scandalized by the idea that Jesus had a human body and soul, and that he willingly lived and ministered by the power of the Holy Spirit rather than his divine nature. This scandal would be remedied, not by coming close to the edge of Apollinaris’ approach, but by a recapturing of the theology of the Cappadocian Fathers and the Christology and pneumatology of John Owen.

Adam Parker is the Pastor of Pearl Presbyterian Church (PCA) and an adjunct Professor at Belhaven University. He is a graduate of Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, MS, and most importantly the husband of Arryn and father of four children.

Related Links

Mortification of Spin: The Mystery of the Incarnation

"A Mystery Beheld" by Joseph Pipa

The Incarnation in the Gospels by Richard Phillips, Philip Ryken, and Daniel Doriani

A Study Guide to John Owen's Communion With God by Ryan McGraw [ Download ]

Intro to the Death of Death in the Death of Christ by J.I. Packer [ Download ]