Episcopalians and Presbyterians Together

Mar 29, 2016

King James VI of Scotland (1566–1625) recorded his advice to Prince Henry (1594–1612), his son and heir, in a 1599 volume entitled Basilikon Doron, “The Royal Gift” (repr., 1887). Amidst other advice on how to operate effectively as a monarch, James warned his son against presbyterians, who had been his chief adversaries for more than a decade. He informed Henry that presbyterians, whom he called “Puritanes, verie pestes in the Church and common-weill of Scotland,” taught that “all Kings and Princes were naturally enemies to the liberty of the Church” (48–49). Presbyterians sought “Paritie in the Church,” which James considered to be the “mother of confusion and enemie to Unitie, which is the mother of ordour” (48–49). He advised Henry to combat the presbyterian “poyson” by advancing learned men to bishoprics and benefices. This would “bannish their Paritie (which cannot agree with a Monarchie)” (50–51).

King James VI of Scotland (1566–1625) recorded his advice to Prince Henry (1594–1612), his son and heir, in a 1599 volume entitled Basilikon Doron, “The Royal Gift” (repr., 1887). Amidst other advice on how to operate effectively as a monarch, James warned his son against presbyterians, who had been his chief adversaries for more than a decade. He informed Henry that presbyterians, whom he called “Puritanes, verie pestes in the Church and common-weill of Scotland,” taught that “all Kings and Princes were naturally enemies to the liberty of the Church” (48–49). Presbyterians sought “Paritie in the Church,” which James considered to be the “mother of confusion and enemie to Unitie, which is the mother of ordour” (48–49). He advised Henry to combat the presbyterian “poyson” by advancing learned men to bishoprics and benefices. This would “bannish their Paritie (which cannot agree with a Monarchie)” (50–51). Pests in the church? Presbyterian Poison? If King James were alive today, he would make a certain presidential candidate with funny hair seemed restrained! Despite his colorful rhetoric, we should not take James’s words against presbyterians too seriously. Like most politicians, he was prone to hyperbole. Above all, James was a pragmatist. Although he likely would not invite presbyterians to a backyard barbecue, he would stand with them against a common enemy, namely, the Roman Catholic Church.

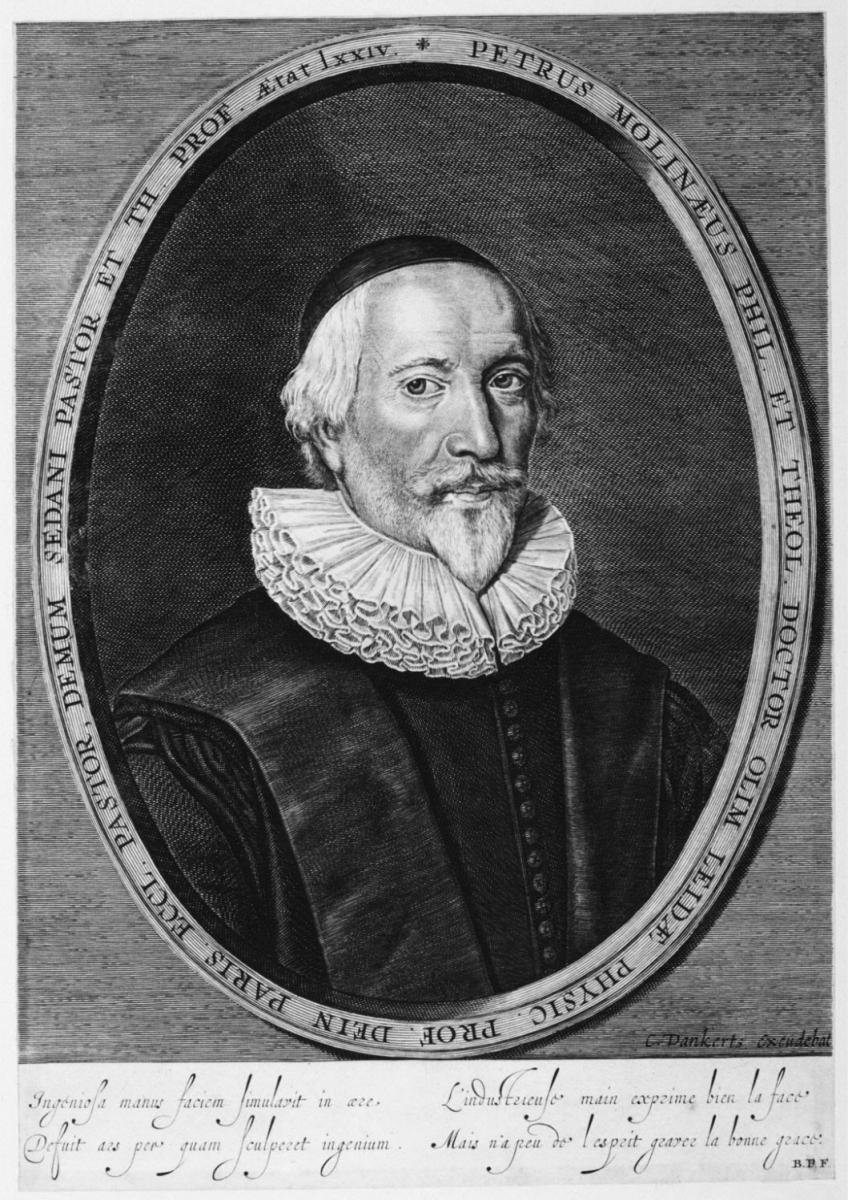

James became king of England in 1603 and, despite his disgust for presbyterian government, began a partnership in 1609 with Pierre du Moulin (d. 1658). This might not seem very significant to us but, at the time, it was kind of a big deal, as Ron Burgundy would say. You see, du Moulin was pastor of the French Reformed congregation in Charenton, near Paris. And the Confession of Faith of the French Reformed churches, developed in 1559 through the influence of John Calvin, outlined a presbyterial (or synodical) form of government. The confession affirmed the parity of all pastors and called for the election of superintendents to govern (articles 30, 32). The French Reformed synods at Gap (1603) and La Rochelle (1607) affirmed the parity of ministers (a feature of church government in direct contrast to episcopalianism) and the permanency of superintendents (J. Quick, Synodicon in Gallia Reformata [London, 1692], i. xiii, 227, 266; J. Aymon, Tous Les Synodes [The Hague, 1710], i. 259, 303). The question is why would a staunch episcopalian like James partner with a presbyterian like du Moulin.

Du Moulin wrote to King James in the dedication to his 1610 work, A Defence of the Catholicke Faith: “We have held it necessary to declare unto the world that that religion which you defend is the same which we professe.” Despite their differences in ecclesiology, du Moulin did not believe that James professed a different religion (or faith). The pastor had come to the assistance of the king in the treatise war that James was waging with Roman Catholic theologians following the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. James, credited with declaring “No bishop, no king,” at the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, overlooked du Moulin’s ecclesiology and enlisted his aid. Prior to reaching out to du Moulin, James only had enlisted theologians within the Church of England to assist him in what became known as the Oath of Allegiance controversy. Du Moulin was the first foreign theologian and, of course, the first adherent of presbyterial government that James commissioned for service. Apparently, du Moulin’s reputation as a formidable polemicist had made its way to the king. James was in the midst of an assault by a seemingly endless number of Roman Catholic theologians, including Cardinal Robert Bellarmine and Cardinal Jacques Davy du Perron, and looked to Reformed churches beyond Britain for aid. The king was able to overlook du Moulin’s presbyterian ecclesiology, which he loathed, in order to join forces against the formidable Roman Catholic threat. The partnership that began as a joint defence of Reformed theology against Roman Catholic assaults would soon transition into a plan to unite all Protestant churches in Europe and, ultimately, to re-form Christendom.

Du Moulin wrote to King James in the dedication to his 1610 work, A Defence of the Catholicke Faith: “We have held it necessary to declare unto the world that that religion which you defend is the same which we professe.” Despite their differences in ecclesiology, du Moulin did not believe that James professed a different religion (or faith). The pastor had come to the assistance of the king in the treatise war that James was waging with Roman Catholic theologians following the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. James, credited with declaring “No bishop, no king,” at the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, overlooked du Moulin’s ecclesiology and enlisted his aid. Prior to reaching out to du Moulin, James only had enlisted theologians within the Church of England to assist him in what became known as the Oath of Allegiance controversy. Du Moulin was the first foreign theologian and, of course, the first adherent of presbyterial government that James commissioned for service. Apparently, du Moulin’s reputation as a formidable polemicist had made its way to the king. James was in the midst of an assault by a seemingly endless number of Roman Catholic theologians, including Cardinal Robert Bellarmine and Cardinal Jacques Davy du Perron, and looked to Reformed churches beyond Britain for aid. The king was able to overlook du Moulin’s presbyterian ecclesiology, which he loathed, in order to join forces against the formidable Roman Catholic threat. The partnership that began as a joint defence of Reformed theology against Roman Catholic assaults would soon transition into a plan to unite all Protestant churches in Europe and, ultimately, to re-form Christendom. This story illustrates that most Reformed Protestants in the seventeenth century did not believe ecclesiastical polity to be a barrier to cooperation. And this was not just a personal belief. Reformed theologians of both presbyterian and episcopalian polities assembled at the Synod of Dort in 1618–19. Presbyterians and Independents, most of whom had ministered within the episcopal Church of England, gathered at the Westminster Assembly in the 1640s.

A point of application for Reformed Protestants today is to reflect on whether or not ecclesiastical polity alone should prevent cooperation between individuals, congregations, and denominations. While the majority of Reformed Protestant denominations have presbyterian (or synodical) government—at least in North America and Western Europe—there are many independent congregations around the world that confess the Westminster Standards or Three Forms of Unity. How can we work together toward a common goal? Furthermore, multiple Reformed churches in Eastern Europe (Hungary, Romania, etc.) have had episcopal polity for centuries. How can we work within their structures to bring a new reformation to these nations? And there are many within the Church of England, such as Lee Gatiss, who could confess much, if not the majority of the Westminster Confession. How can we encourage them in their efforts to return their church and nation to a commitment to the Word of God?

The partnership of King James and Pierre du Moulin can serve as a model for both episcopalian and presbyterian (okay, fine, and independent!) Reformed Protestants of today in combatting the common enemy of false religion in its various forms.

The partnership of King James and Pierre du Moulin can serve as a model for both episcopalian and presbyterian (okay, fine, and independent!) Reformed Protestants of today in combatting the common enemy of false religion in its various forms. In a future post, we'll explore how James and du Moulin envisioned this in their time.

__________

Mr. Dan Borvan

Keble College, Oxford

Under Care of the Presbytery of the Midwest, Orthodox Prebyteryian Church

Co-founder, John Owen Society