Sybil Mosely Bingham and the Challenges of Missionary Life in Hawaii

Sybil Mosely Bingham and the Challenges of Missionary Life in Hawaii

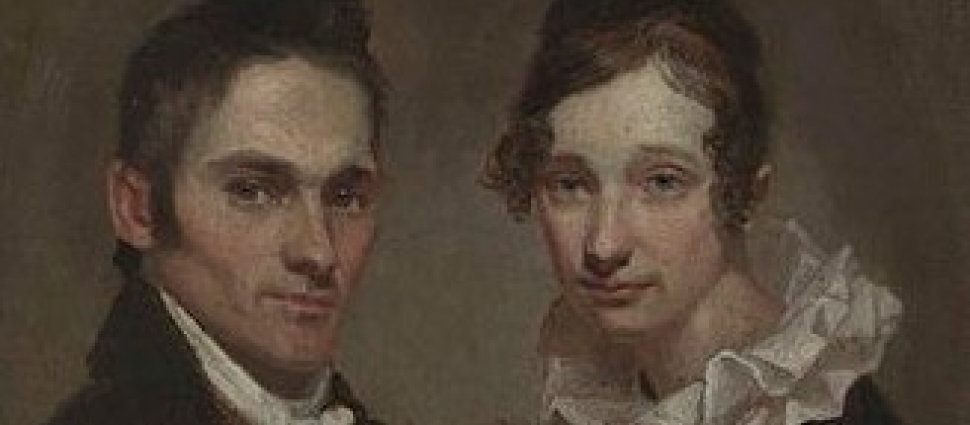

Sybil’s admission to the mission field reminds me of a scene of a movie. She was asking for directions to her accommodations when a young man offered to take her there. The man, Hiram Bingham, was preparing to leave as a missionary to the Hawaiian Islands. He just had one problem: the mission board was reluctant to send unmarried people, and his fiancée had just broken off their engagement.

Sybil was a school teacher dreaming of joining a mission. It was common then for young Christian women to seek “higher” service to God by marrying a minister, going to a mission field, or both.

And there they were, in the same vehicle, both thinking of far-off fields. “I had taken cold by a night’s ride over the mountains,” Hiram explained, “and I wrapped a handkerchief about my neck, chin, and mouth, that cold evening, and this awakened ready sympathy in the sensitive heart of the young lady.”[1]

Hiram had heard of a young girl described as “a most amiable and thoroughly qualified companion for a missionary.” During the ride, Hiram’s “mind was intently querying whether this could be the very same.”[2]

When they arrived at their destination, they spoke for a while by the fire. “I measured the lines of her face and the expression of her features with more than an artist’s carefulness,”[3] Hiram wrote.

After discussing the matter with other men, Hiram asked a friend to contact Sybil and ask for an audience. The friend explained the matter to Sybil, leaving her with a verse meant to make a rejection rather difficult: “Rebecca said, ‘I will go” (Genesis 24:58).

But Sybil had no intention of rejecting Hiram’s proposal. She had been waiting for such an opportunity. And there was also a spark of romance. “Since that memorable evening when I was introduced to him, I find that he has secured my love,” Sybil wrote her sister. “God did indeed choose for me.”[4]

She and Hiram married less than two weeks later. On October 23, 1819, they sailed with seven other missionary couples on the Thaddeus, bound for Hawaii.

An Unfamiliar World

The 18,000-mile voyage was difficult, with the missionaries cramped in a small space, most suffering from seasickness – which might have been worse for Sybil and three other women who got pregnant during the trip. She also felt “like a pilgrim and a stranger” with “no abiding place,”[5] while everything she had loved on this earth moved further away.

The ship landed at Kailua-Kona, Big Island, on April 4, 1820. Before Sybil could even leave the boat, however, she had a first inkling that missionary life was not going to be what she had imagined. Before her departure, the secretary of the American Board of Foreign Missions (ABFM) had laid out the missionaries’ great commission. Besides preaching and translating, they were “to aim at nothing short of covering those islands with fruitful fields and pleasant dwellings, and schools and churches.”[6] Instead, the women’s first task was to sew western clothes for Queen Kaahumanu.

At that time, Queen Kaahumanu ruled together with King Liholiho (Kamehameha II). Recent converts to Christianity, they had put an end to the traditional religious system. For the missionaries, this was good news. At the same time, the rulers were concerned about the seemingly unending arrival of foreigners. A Hawaiian young man who had been to China reported that the people there were afraid the foreigners would take over the country. Could that happen to Hawaii?

The missionaries showed they carried no weapons and insisted they meant no harm. What apparently convinced the rulers was the presence of the women, since conquering soldiers would not take their wives along. Some time later, one of the missionary wives, Lucia Holmes, remarked: “It has been thought by some that they would not have gotten permission to land had it not been for the females.”[7]

Wife, Mother, Teacher, and Friend

In spite of their rough start, Sybil set up the first missionary school in Hawaii – initially in the twenty-feet-square home provided by the government to the thirteen missionaries and their babies (the king refused to allow foreigners to build a house on his land).

Like most missionary wives, she juggled her responsibilities as a wife, mother, and teacher. On top of that, the queen and other chiefs continued to request clothes. The home was also crowded with visitors who came out of curiosity to observe a western lifestyle. They were particularly intrigued by the amount of work these western women performed.

And these women had really placed a lot on their plates. “I could never have conceived when thinking of going to the heathen to tell them of a Saviour, of the miscellany of labor that has actually fallen to my portion,” Sybil wrote to her sister. “There are those on missionary ground who are better able to realize their anticipations of a systematic work, but not a mother of a rising family placed in a post like this.”[8]

“My exhausted nature droops,” she wrote in her journal. “I sometimes grieve that I can no more devote myself to the language and the study of the Bible. But I do not indulge myself in it. I believe God appoints my work and it is enough for me to see that I do it all with an eye to his glory. Perhaps my life will be spared to work yet more directly for the heathen.”[9]

And working directly she did. In fact, in 1821, when Kaahumanu became so sick that everyone had given up hope, it was Sybil who “sat down by the side of the sick queen and with unfeigned sympathy for her sufferings and danger, bathed her aching temples.”[10] All this, while speaking to her about Christ and the Christian’s hope after death.

Eventually, the queen recovered (Hiram credits his wife’s care for this) and continued to be a good friend to Sybil. In fact, her attitude changed also in other ways. “There was from this period a marked difference in her demeanor toward the missionaries,” Hiram wrote, “which became more and more striking, till we were allowed to acknowledge her as a disciple of the Divine Master.”[11]

The Binghams stayed in Hawaii for twenty years and founded the Kawaiahaʻo Church. They also helped to develop a written Hawaiian alphabet. Besides the school, Sybil also started a weekly prayer meeting, attended by more than a thousand Hawaiian women.

In the course of time, however, her frail body began to fail and the couple returned to New England. It was supposed to be a furlough, but her health didn’t improve, and she was finally diagnosed with “consumption.’” She died on February 27, 1848 in Easthampton, Massachusetts.

Some of her children went back to Hawaii to continue their parents’ work: her son Hiram and her daughters Lizzie and Lydia, who helped establish a female academy in Honolulu. Speaking to his son Hiram III, who became an explorer and politician, Hiram II said, “If ever there was in this world a woman who was noble, honest, generous, loving, tender-hearted and sympathetic, that woman was your grandmother.”[12]

[1] Augustine George Hibbard, History of the Town of Goshen, Connecticut: With Genealogies and Biographies, Hartford, 1897, 260

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Peter T. Young, “Sybil’s Bones,” Images of Old Hawaii, https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/sybils-bones/

[5] Jennifer Thigpen, Island Queens and Mission Wives: How Gender and Empire Remade Hawai‘i’s Pacific World, The University of North Carolina Press, 2014, 46

[6] Thigpen, Island Queens and Mission Wives, 43

[7] Patricia Grimshaw, Paths of Duty: American Missionary Wives in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press, 1989, 41

[8] Dana L. Robert, American Women in Mission, 60

[9] Dana L. Robert, American Women in Mission: A Short History of the Thought and Practice, Mercer University Press 1996, 60

[10] Hiram Bingham, A Residence of Twenty-one Years in the Sandwich Islands, Hartford 1848, 149

[11] Bingham, A Residence of Twenty-one Years, 149.

[12] Peter T. Young, “Sybil’s Bones,” Images of Old Hawaii, https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/sybils-bones/