Wednesday @ Westminster: One Bible, Two Testaments

Sep 7, 2016

For many of us who have discovered the Reformed expression of the Christian faith after years in other traditions, “covenant theology” was one of the most eye-opening facets of it. It was more than just another part of theology, though. It was like getting a new pair of glasses. The old way we saw the Bible with Israel in the Old Testament and the Church in the New Testament was like an old, worn out pair of glasses with scratches and lots of scuff marks. This new pair allowed us to see clearly that our one Bible has two complementary testaments.

For many of us who have discovered the Reformed expression of the Christian faith after years in other traditions, “covenant theology” was one of the most eye-opening facets of it. It was more than just another part of theology, though. It was like getting a new pair of glasses. The old way we saw the Bible with Israel in the Old Testament and the Church in the New Testament was like an old, worn out pair of glasses with scratches and lots of scuff marks. This new pair allowed us to see clearly that our one Bible has two complementary testaments. Of course many will say that this is a theological grid that we’ve imposed upon the Bible. We can take heart, though, that our ancient forefathers such as Justin Martyr and the Epistle of Barnabus viewed the scriptural understanding of its own diversity within unity. During the Reformation men such as Heinrich Bullinger and John Calvin read the Bible in this way to explain how Old Testament saints were saved and why we baptize children, speaking of the one covenant of grace despite varied times and places in which that covenant was expressed.

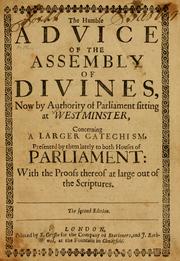

The Westminster Larger Catechism follows this ancient Christian and classic Protestant way of reading the Bible, of seeing God’s one story with its various acts. What it says is that we have One Bible, Two Testaments.

Its Unity

First, when you read your Bible, recognize its unity. There is one covenant of grace, that is, one plan and story of God the Creator becoming the Redeemer of sinful humanity.

One example of this is in Romans 11. In seeking to answer the conundrum that because most Jews rejected Jesus this meant God’s promises failed, Paul gives two images to describe God’s ancient promises to the Israelites and the fulfillment of them to the Gentiles: “If the dough offered as firstfruits is holy, so is the whole lump, and if the root is holy, so are the branches” (Rom. 11:16). These images both are meant to impress upon us the unity of God’s work from ancient times through the present.

The first image is that of bread. If the firstfruits of the dough is holy, then the entire batch of bread is holy. There is one batch of dough. Like a baker, God cuts off the first portion to make a loaf; if it is acceptable, then the entire batch will be acceptable. This is his way of saying that God has one plan of salvation. Those whom he called to be his holy people, beginning with Abram, and all those to follow partake of the same calling, the same salvation.

The second image is that of a tree. If the roots of a tree are holy, then the entire trunk and branches are holy. The roots are the patriarchs; the branches are all who draw nourishment from them. Paul goes on to explain in more detail this image in verses 17–24. Despite the fact that there are two kinds of branches, natural (Jew) and wild (Gentile), the wild branches that are grafted onto the tree in place of those natural branches pruned off because of unbelief partake of the same roots.

The theological truth of this is that when we read our Bibles from Old through the New Testaments, we are reading the story of one God, one Savior, one means of salvation through faith, and therefore one people despite their chronological, geographical, and racial differences.

Its Diversity

This is not to diminish diversity. This one covenant of grace is administered by God and lived by his people in distinct ways throughout the story of the Bible. As the Catechism says, “The covenant of grace was not always administered after the same manner, but the administrations of it under the Old Testament were different from those under the New” (Q&A 33).

In the Old Testament

When the Catechism speaks of “the Old Testament” it is speaking of everything in the story prior to the coming of Christ, from God’s first promise in Genesis 3:15 through the prophets who preached of the coming Savior.

“How was the covenant of grace administered under the Old Testament?” (Q&A 34) It was administered “by promises.” For example, the promise of the seed of the woman to come (Gen. 3:15) gave hope of restoration; the promise that all the nations would be blessed through Abram’s seed (Gen. 12) gave hope for all the world to partake of salvation. It was administered “by prophecies.” Isaiah prophesied a Savior to come who would be God with us (Isa. 7:14). Jeremiah prophesied a Savior to come who would be his people’s righteousness (Jer. 23:6). Ezekiel prophesied a Savior to come who would be his people’s king and shepherd (Ezek. 37:24). It was administered “by sacrifices,” such as the offering of the firstborn (Ex. 12), the daily morning and evening sacrifice (Num. 28), the ongoing sacrifices by the people for their sins (Lev. 1–7), and the annual Day of Atonement (Lev. 16). It was administered “by circumcision.” This was the ritual that the Lord prescribed to Abraham and continued throughout the generations of the Israelites as the means by which his people was distinguished from the nations (Gen. 17). It was administered “by the Passover.” This was the sacrifice and meal before the exodus from Egypt that was remembered yearly by all Israelites (Ex. 12).

All of these means of the Lord administering his covenant of grace with his ancient people “fore-signif[ied] Christ . . . to come.” And all of these “were for that time sufficient to build up the elect in faith in the promised Messiah, by whom they then had full remission of sin, and eternal salvation.”

In the New Testament

In the New Testament, “when Christ the substance was exhibited” (Q&A 35), we have the reality of all the promises concerning the Messiah. We have the fulfillment of the prophecies concerning his coming. We have the accomplishment of the once for all sacrifice. We have the end of circumcision. And we have the perfect Passover lamb in Jesus Christ.

The substance of the covenant of grace is the same in both Testaments, but how is the one covenant of grace now administered? It is administered in two basic, ordinary, simple, and unadorned ways: preaching of the Word and the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

This gets to the heart of a struggle we may have as Christians. When we read our Old Testament, we may ask ourselves, “Why doesn’t God show himself visibly like he did then? Why doesn’t he just thunder his voice from heaven? Why doesn’t he show us dramatic signs and wonders anymore?” What we need to learn again and again is the irony that although the Word and sacraments are ordinary means, as the Catechism says, in them “grace and salvation are held forth in more fulness, evidence, and efficacy, to all nations” (Q&A 35). We no longer need the dramatic; the drama has been performed in the life of our Lord Jesus Christ. When we come to that realization, we use the new pair of glasses God has given us in seeing the one story through all the twists and turns. Thank him that you now live in this age of fulfillment. Take advantage of your situation. Read the one story, meditate upon the one Savior’s action in it, and find your place in the story as a participant.