Episcopalians and Presbyterians Together...Again

Jun 2, 2016

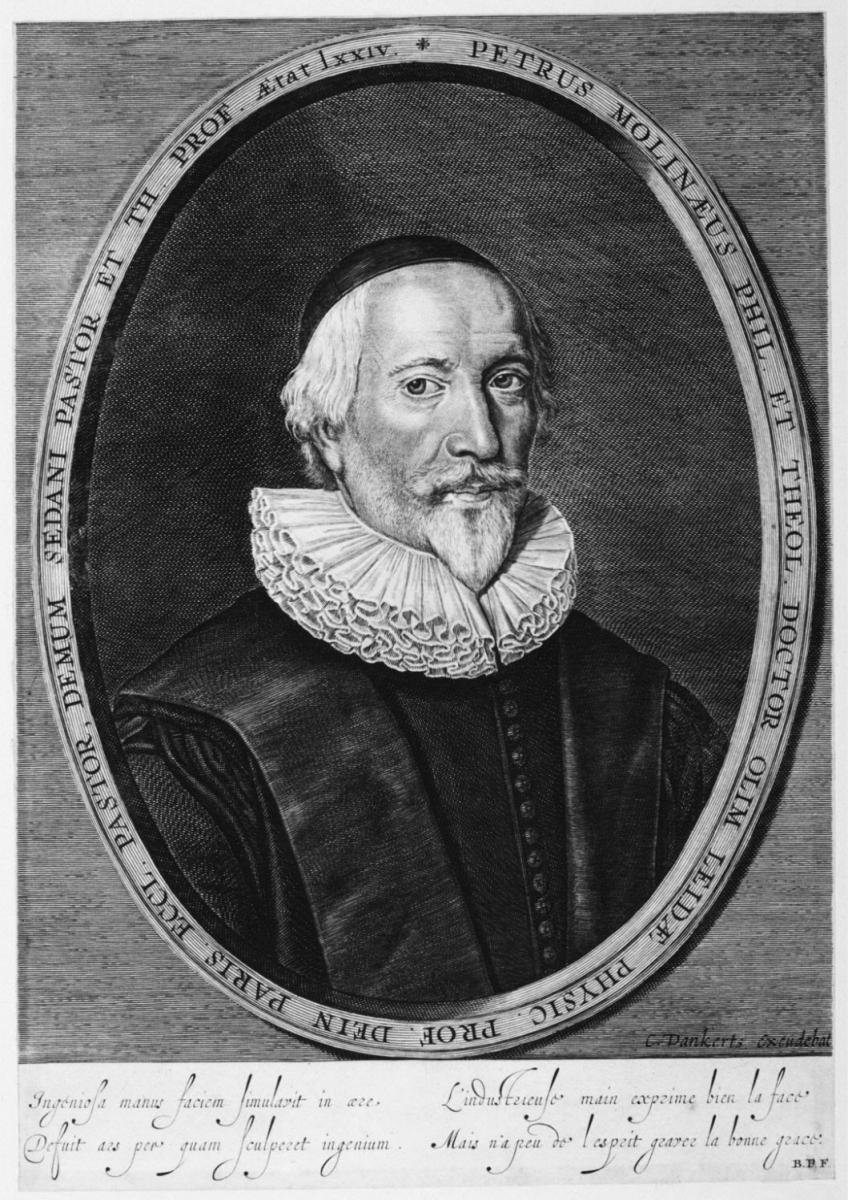

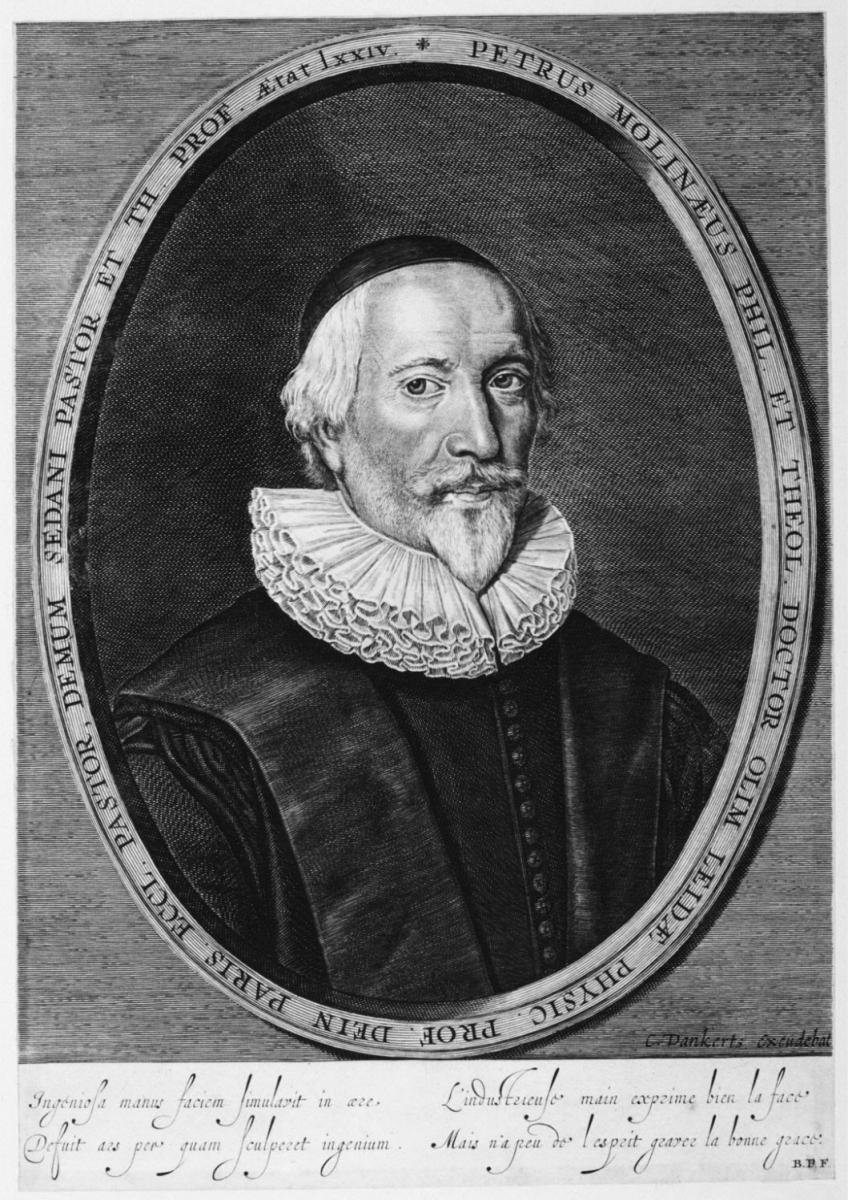

In my first post I recounted that King James I and VI of England and Scotland (1566–1625), a staunch episcopalian and despiser of presbyterians, partnered with Pierre du Moulin (d. 1658), pastor of the French Reformed congregation in Paris and defender of presbyterian government, to combat Roman Catholic apologists. The unlikely partnership soon expanded its mission and adopted a most ambitious (and possibly hare-brained) goal of the reunion of Christendom (Spoiler alert...they failed).

In my first post I recounted that King James I and VI of England and Scotland (1566–1625), a staunch episcopalian and despiser of presbyterians, partnered with Pierre du Moulin (d. 1658), pastor of the French Reformed congregation in Paris and defender of presbyterian government, to combat Roman Catholic apologists. The unlikely partnership soon expanded its mission and adopted a most ambitious (and possibly hare-brained) goal of the reunion of Christendom (Spoiler alert...they failed). King James first expressed his desire for ecclesiastical reunion in his initial speech to parliament as King of England in March 1604. He declared that he longed to be "one of the members of such a generall Christian union in Religion, as laying wilfulnesse aside on both hands, wee might meete in the middest, which is the Center and perfection of all things" (J. P. Sommerville, ed., King James I and VI: Political Writings [Cambridge, 1994], 140). Six days later, Philippe du Plessis-Mornay (1549-1623), the grand statesman of the Huguenots, wrote to Robert Le Maçon (1534/5-1611), pastor of the congregation of French refugees in London, and related the activity of the recent Synod at Gap (1603). Du Plessis-Mornay reported that many of the delegates to the synod were delighted to see James ascend the throne of England and that they hoped his rule would produce a great advancement in the church of Christ, particularly the reunion of all the Reformed Churches of Europe (Du Plessis-Mornay, Mémoires et correspondence de Duplessis-Mornay [Paris, 1824–5], ix. 544). The French Reformed churches had been pursuing unity with other Protestants since their 1578 national synod at Sainte-Foy. Nearly every subsequent national synod until 1612 approved activity related to Protestant ecumenism, including the proposal of a general synod of Reformed churches and the call for collaboration on a joint confession (J. Quick, Synodicon in Gallia Reformata [London, 1692], i. 120–122, 153, 143–144, 180, 239; J. Aymon, Tous Les Synodes [The Hague, 1710], i. 131–133, 157, 170, 201, 274). The national synod at Gap sent letters to universities in England, Scotland, Heidelberg, Basel, Geneva, and Leiden asking for their cooperation in this pursuit of Protestant union.

In a March 1613 letter to King James, Pierre du Moulin listed twenty steps for uniting Protestantism. He proposed an initial gathering of two theologians from each state. At this meeting, the theologians would place all the Reformed confessions on a table and then compose a new one. The unified confession would be limited to matters they considered necessary for salvation. For example, it would not address Arminius’s teaching on predestination and the perseverance of the saints. Du Moulin believed that formulating a new confession would not cause much difficulty because the churches already agreed on the essential faith. Their only differences were related to polity and ceremony. To prevent any discord in these areas, each delegate would declare that his church would not condemn the other churches over these differences. King James was to oversee the meeting from afar and offer advice through messengers. Following the successful conclusion of the conference, all the delegates were to travel to England to offer their respects to James. In a later proposal du Moulin included a second meeting between the unified Reformed and Lutherans. The two parties would focus on matters on which they agreed and set aside issues of major disagreement, namely the sacraments. With all of Protestantism united, du Moulin expressed his final goal of an ecumenical council for the purpose of reconciliation with the Roman Catholic Church. Du Moulin did not provide much detail as to the nature of the reconciliation but instead chose to focus on the exciting thought of a reunion of Christendom. Of course, a new Christendom require a new Constantine. King James was more than happy to assume that role in du Moulin’s plan.

Du Moulin’s modified plan for union was submitted to the national synod of the French Reformed churches at Tonneins in 1614. He and King James continued to develop the plan leading up the international Synod at Dort in 1618. Du Moulin hoped that this synod would provide an opportunity for the presentation of his plan of union. He and his committee planned to attend until King Louis XIII of France barred them from leaving the country. Du Moulin submitted a proposal for the synod to implement portions of his plan for union, particularly the formulation of a joint confession and an invitation to Lutherans for dialogue. Unfortunately for James and du Moulin, the synod quietly dropped the matter. The plan for Protestant union got lost in the controversy involving Jacobus Arminius, du Moulin’s former college at the University of Leiden. Even if du Moulin had been allowed to attend the synod the outcome of his plan for reunion probably would have been the same.

What can we learn from Pierre du Moulin’s ill-fated plan for Christian reunion? I cannot address in a short blog post the infinite number of doctrinal and political complexities involved in his scheme to unite all Protestants and then all Protestants and Catholics, so I only will offer my thoughts on his goal of joining together all Reformed churches.

First, we must admire du Moulin’s commitment to Reformed ecumenism. He believed that close cooperation would strengthen the churches both internally and externally. The many avenues of Reformed ecumenism available to us today involving individual congregations, presbyteries/classes, and denominations/federations, offer numerous opportunities for spreading the gospel and strengthening our churches. Unlike early modern Reformed churches, who zealously pursued unity despite hindrances of war, rampant disease, and primitive communication and transportation, our relative peace and prosperity provide us much more freedom to pursue cooperation. Modern technology allows us to partner with churches on the other side of the world.

Second, we must avoid du Moulin’s minimization of doctrinal differences while pursuing unity. While du Moulin’s desire for a joint confession is commendable, his plan to avoid discussion of Arminian teaching in order to produce the confession is not. Du Moulin certainly was aware of the errors in Arminian theology. He produced The Anatomie of Arminianisme (1619). nity at the expense of doctrine is no unity at all, however. Many in the broadly Reformed world today pursue superficial unity with groups that reject foundational elements of the Reformed confession. To what end? Superficial unity dangles before us the gleaming prize of influence in political and cultural arenas. The influence never materializes, though, and we eventually realize that we have sold our Reformed birthright for a bowl of soup. True unity only comes through doctrinal agreement. After du Moulin recognized his great failure in pursuing influence through King James in his union with Arminians, he devoted himself to correcting the doctrinal errors of Arminianism, Amyraldianism, and others -isms rather than pretending they were insignificant.

Would that we would follow his example.