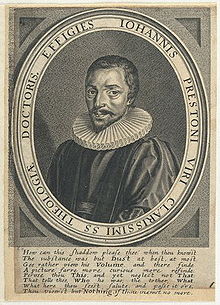

Puritan Preachers: John Preston

Jul 14, 2017

We conclude our series on Puritan preachers (see #1, #2, #3) with John Preston (1587–1628), whose preaching can be described as preaching great gospel themes. He was more topical and organized by theological categories and questions than the verse-by-verse biblical expositions of John Calvin. Hughes Oliphant Old wrote:

We conclude our series on Puritan preachers (see #1, #2, #3) with John Preston (1587–1628), whose preaching can be described as preaching great gospel themes. He was more topical and organized by theological categories and questions than the verse-by-verse biblical expositions of John Calvin. Hughes Oliphant Old wrote:The text is studied briefly in order to draw out of it a specific teaching or theme, and then this theme is developed in a number of points which are then supported by various arguments, drawn mostly from Scripture. They are illustrated by examples or illuminated by similes. Then, finally, they are applied to the lives of the congregation. In this respect Preston’s sermons resemble those of medieval Scholasticism. . . . Preston usually takes one verse and develops from it a theme or a number of themes (The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, 4:284).

We see an example of this method in The Breast-Plate of Faith and Love (1630), which is a classic statement of Puritan spirituality (see Old, Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures, 4:280–86). In the first section of the book, Preston preaches four sermons (117 pages) on a single text, Romans 1:17: “For therein is the righteousness of God revealed from faith to faith: as it is written, The just shall live by faith.” He opens three doctrines: (1) that righteousness is revealed and offered in the gospel to as many as will take it, (2) that by faith we are made to partake of this righteousness, and (3) that faith has degrees, and every Christian should grow from one degree to another. We can see that Preston derives these doctrines from the text, but he spends little time in his sermons studying the meaning of the text. Rather, he moves quickly to ask questions about each doctrine, which he answers from other Scripture passages. In his first point about the righteousness revealed in the gospel, he queries: (1) Why is this righteousness revealed? (2) How does this righteousness save? (3) How is it offered to us? (4) To whom is it offered? (5) Upon what qualifications is it offered? (6) How is it made ours? (7) What is required of us when we have it? These questions are followed by two warnings to those who reject Christ or put off receiving Him, and then by three exhortations to receive Christ.

The result is clear, applied preaching of the gospel. Old commented: “These sermons may properly be regarded as evangelistic sermons. Their aim is the conversion of those to whom they are addressed. Preston is fully aware that he is preaching to baptized Christians, but he is concerned that his congregation enter into the full reality of which their baptism is a sign and a promise” (Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures, 4:281). Addressed to those inside the church, Preston’s evangelistic teaching focuses on the meaning of conversion so as to distinguish between true believers and mere nominal Christians.

In a sermon series based on 2 Timothy 1:13, A Pattern of Wholesome Words, Preston lays out some of his views of the work of the preacher. Irvonwy Morgan observes that here too we see Preston starting with a doctrine and then developing it by answering questions and objections. He says that preachers should generally avoid quoting the church fathers, though some exceptions may be allowed for more recent writers, such as Calvin. But they should study broadly in human learning and digest the material well so that they can preach the same truths simply and usefully, much as livestock eat hay but produce wool and milk fit for men (Morgan, Puritan Spirituality, 12–14.).

The preacher is an ambassador who speaks for God to the people as His public representative. He must interpret the Word by raising a doctrine from the text, supporting it with confirming Scripture passages, then making application of it to particular kinds of people. The text must be understood according to proper grammar; rhetorical devices, such as metaphors; the “scope” or purpose of the text; and the analogy of faith. Each sermon must be applied by deriving its inherent uses. In these things, Preston sounds very much like Perkins in his Arte of Prophecying. One also senses his medical training in the background as he describes how the preacher must apply a different cure to the fever of lust, the swelling of pride, the palsy of anger, the lethargy of idleness, the humor of vainglory, the pleurisy of security, and the unsavory breath of evil speech (Morgan, Puritan Spirituality, 13–14. “Humor” here probably refers to an imbalance in bodily fluids, which in the medicine of that time were believed to produce the temperaments of melancholic, choleric, phlegmatic, and sanguine). General applications are not nearly as helpful as speaking to specific sins.

The minister must preach the Word. Preachers should feed their flocks, preaching the Scriptures at least twice on the Sabbath and also catechizing. Morgan says, “The Word must be presented in a spiritual manner, plain and unadorned, and easy to follow” (Morgan, Puritan Spirituality, 14). However, the sermon should not be just a running commentary on the Bible, but a structured discourse with distinct points. It is said that the stones of the walls of Byzantium were fitted so closely together that the wall appeared as one stone. Preston quips, “This may be a commendation in a wall, but not in a sermon.” Also, beware of filling your sermon with material foreign to the Scriptures. Children may think that weeds in a cornfield are pretty, but the farmer knows they make it less fruitful. Even in making illustrations, the best material can be found in the Bible itself, though other illustrations are permissible so long as they do not merely please weak and flighty minds. We have already seen a number of Preston’s own extrabiblical illustrations (Morgan, Puritan Spirituality, 14–15).

In all things, the preacher operates as an instrument of the Spirit of Christ. He is totally dependent upon the Lord for any good results to come of his preaching. Preston says:

When Christ showeth himself to a man, it is another thing than when the ministers shall show him, or the Scriptures nakedly read do show him: for when Christ shall show himself by his Spirit, that showing draweth a man’s heart to long after him, otherwise we may preach long enough, and show you that these spiritual things, these privileges are prepared for you in Christ, but it the Holy Ghost that must write them in your hearts; we can but write them in your heads (The Breast-Plate of Faith and Love, 1:163).